Personality and values are important variables for understanding the person, and many studies done in various countries and cultures have examined the relationship between these two attributes with the aim of developing an integrative model for enriching our understanding of the individual (Parks-Leduc, Feldman, & Bardi, 2015). Most commonly used survey instruments are Schwartz’s Value Survey and the Big Five trait measurement. Schwartz’s value theory was developed with an etici approach and is found to have near universality across cultures (Cieciuch, Schwartz, & Vecchione, 2013; Schwartz, 1994). Big-Five, on the other hand, “has shown itself to be reliable, valid and useful in a variety of contents and cultures” (McCrae & Costa, 2004, p. 592) and is found to be universal across cultures (McCrae & Costa, 1997). The first aim of the present research is to examine the trait-value relationship using instruments developed in Turkey with an emic perspective and to see if the links found with instruments of universal usage will be replicated with Turkish indigenous measures and if value and trait items are representative of communal and agency conceptions. Meanwhile, restriction of economic resources was found to have a moderating effect on the strength of value-trait relationships (Fischer & Boer, 2015). Our second aim is to test if the amount of disposable income effects value-trait links measured with indigenous instruments.

Similarities and Differences Between Values and Personality Traits

Personality and values are two areas of different psychological disciplines. Values are studied in social psychology, whereas personality is a research area of personality and individual differences, however, they are associated concepts (Parks & Guay, 2009; Parks-Leduc et al., 2015; Roccas, Sagiv, Schwartz, & Knafo, 2002). Correlational studies infer common genetic factors for values and personality traits (Schermer, Vernon, Maio, & Jang, 2011). Furthermore, Rokeach (1973, p. 21) had called attention to the common descriptive terms when he stated that a person’s character, which is seen from a personality psychologist’s standpoint as a cluster of fixed traits, can be reformulated from an internal, phenomenological standpoint as a system of values. Thus, a person identified from the “outside” as an authoritarian on the basis of his F-scale score can also be identified from the “inside” as one who values obedience, cleanliness, and politeness and undervalues broad-mindedness, intellectualism and imagination. It is not uncommon to run into terms shared by both concepts. For instance, the term obedience may both be a tendency or a belief about the importance of being obedient to elderlies or to authority. However, this does not mean that valuing obedience will lead to obedient behavior (Sheldon & Krieger, 2014).

In spite of some similarities, there are important distinctions between the two constructs. Personality traits relate to what we naturally tend to do, while values relate to what we believe we ought to do. Values are ordered by importance and may conflict with each other when activated simultaneously, so that value priorities may change if exposed to new environments but personality traits are relatively stable. Values include an evaluative component while personality traits do not. Moreover, values as life goals may drive behavior (Fischer & Boer, 2015) and being cognitive representations of motivations affect behavior under volitional control, but traits are linked to temperament and describe what people are like (Fischer & Boer, 2015; Parks & Guay, 2009; Roccas et al., 2002). Hence, links found in correlative studies between personality traits and values are not perfectly systematic; there is variability in the outputs of empirical studies. However, differences between the measurements used could be one of the reasons for this variability. Meta-analytic studies on value-trait links done by Fischer and Boer (2015) and Parks-Leduc et al. (2015) include only those studies using Schwartz’s value measurement (SVS and PVQ) and the Big Five trait measurement. The present study examines value-trait relationships on the basis of these two studies.

Values, Traits and Their Association With Agency-Communion

Schwartz’s value measurement, which consists of power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, universalism, benevolence, conformity, tradition and security as 10 value types, is found to be near universal across cultures. The ten main values are related in a circular pattern and the values are organized in two bipolar dimensions, which are openness to change vs. conservation and self-enhancement vs. self-transcendence. Openness to change and self-enhancement incorporate individual interest, while their opposites, conservation and self-transcendence incorporate social interest (Schwartz, 2012). The circular structure is formed through the conflict of opposite poles and compatibility among adjacent values. So outside variables related to a value are similarly related with the adjacent values and the relationship gets weaker as the value type departs from the most positively related value. However, the relationship is not linear, but sinusoidal (Schwartz, 1992, 1996) described as smoothly fluctuating curves.

Meanwhile, a recent study by Trapnell and Paulhus (2012) shows that Schwartz’s values are also related to the importance people place on agency and communion, referred by Bakan (1966) as two fundamental modalities of human existence. Hogan (1983) labels them as “getting ahead” (agentic) and as “getting along” (communion). Agentic content refers to goal achievement and task functioning like competence, assertiveness and persistence. Communion content refers to relationship and social functioning like helpfulness, benevolence, trustworthiness and cooperativeness (Abele & Wojciszke, 2014). Two basic motives of these two dimensions are Approval and Power (Paulhus & John, 1998). These two factors encompass various two fold conceptualizations in psychology such as instrumentality vs. expressiveness, masculinity vs. femininity, independent vs. interdependent, initiating structure vs. consideration, etc. (Abele & Wojciszke, 2014). Schwartz’s (2012) differentiation of values as personal focused vs. social focused was also revealed in Trapnell and Paulhus’ (2012) study, in order to be interpreted in the agentic and communion framework. The data collected from the premier European Social Survey (ESS) revealed that self-transcendence and conservation values locate at the communion dimension, whereas self-enhancement and openness to change values locate at the agentic dimension.

On the other hand, personality traits are described as recurrent patterns of thought, behavior and affect, so they vary in the extent to which they are based to cognition (Parks-Leduc et al., 2015). The Big-Five trait measurement consists of neuroticism (emotional stability), extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience (intellect) as five traits. The fifth factor is the broadest factor including interests in all aspects of life, such as thoughts, ideas, experiences, feelings, art and intellectual curiosity (Olver & Mooradian, 2003). This five-factor structure is also found to be universal across cultures (McCrae & Costa, 1997). The agentic and communion constructs are also attributed to differentiate personality traits (Paulhus & Trapnell, 2008; Trapnell & Wiggins, 1990). Agency attributes are positively related to openness to experience and negatively related to agreeableness and conscientiousness. Communion attributes, on the other hand, are positively related to extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness (Diehl, Owen, & Youngblade, 2004). When we bring together the findings of Trapnell and Paulhus (2012) and Trapnell and Wiggins (1990) studies, we can expect agentic natured values and agentic traits to be related to each other while communal natured values and communion traits to be associated with each other.

For the value-trait association, Parks-Leduc et al. (2015) propose two sources of similarities, which strengthen the links between specific traits and values: the nature and the content of the two constructs. Specific traits, which are more cognitive in nature and content, tend to have stronger links with values, but affective natured traits may have weaker links. For example, the contents of the trait openness to experience and the value openness to change are matching. Both include preference for new ideas, new experiences, stimulation, curiosity, creativity and self-direction. Thus, the trait openness to experience, is found to have the strongest link and emotional stability, the lowest link with values (Fischer & Boer, 2015; Parks-Leduc et al., 2015). Here, we again see a two-fold conceptualization: cognitive-natured vs. affective-natured concepts.

In both meta-analytic studies using Schwartz value and the Big Five trait measurement (Fischer & Boer, 2015; Parks-Leduc et al., 2015) the strongest positive association is found between openness to experience trait and the higher order value openness to change (especially with self-direction). The second consistent positive association is between the personality trait agreeableness and socially oriented values such as benevolence and conformity. The structural pattern of the value theory also works with this trait-value link (Parks-Leduc et al., 2015). That is, the links of traits are negative with the opposite ends of the same major dimensions (agreeableness conflicts with self-enhancement and openness to experience/intellect with conservation) as proposed in the value theory. Contrary to the assumption of the oppositions of bipolar values in Schwartz’s model, agency and communion value dimensions are not opposites in agentic-communion model. According to Wiggins (Trapnell & Paulhus, 2012, p. 43) various combinations are “possible in a society or in an individual: Development of one modality does not restrict development in the other; there is no inherent conflict between the two”. On the contrary they moderate each other (Abele & Wojciszke, 2014).

The findings of the two meta-analytic studies (Fischer & Boer, 2015 and Parks-Leduc et al., 2015) and of findings collected from the two sources of data (Trapnell & Paulhus, 2012) are acquired from two scales (i.e., the Big Five and Schwartz’s value scales), which are near universal across cultures. According to Parks-Leduc and colleagues, similarity of the nature of the two constructs is important in the value-trait relation. This means stronger links are expected between cognitive natured traits and values as well as between affective natured traits and values. It will be challenging to explore the conceptual similarities of the trait-value links measured with indigenous instruments. It will also be interesting to see how indigenous value and trait items are composed under agency and communal conceptions. So, one of the goals of this study is to inspect the conceptual similarities in the links between traits and values.

Moderating Variables in Value-Trait Links

The two meta-analytic studies also examined value-trait relationships with a moderating variable. Parks-Leduc et al. (2015) examined the role of individualism-collectivism and tightness-looseness of culture as moderators. The data collected for the moderating variable is based on Hofstede’s 1980 data in which countries are assigned a number from 1 to 100 representing their level of individualism versus collectivism and level of tightness versus looseness. Neither of these cultural variables was found to be effective on the relationships between traits and values. However, there is a long lapse of time between 1980 and 2015 studies. Maybe current data collected for the same cultural variables for each country would give different results.

Fischer and Boer (2015), on the other hand, examined the contribution of restricting threatening contexts as moderators on the strength of value-trait links. These moderators are resource threat (measured by gross national income), ecological threat (measured predictors are: population pressure, air quality, human sustenance and death, infant mortality etc.), and restrictive social institutions (measured predictors are: autocracy, crime rate, press freedom, labor freedom etc.). In high threatening contexts, all personality traits, except extraversion were found to have weaker correlations with values. Personality traits and value links were found to get stronger with low financial, low ecological threats and with high democratic social contexts. These findings are an important contribution to theoretical explanations of value-personality association, which challenged us to examine the moderation effect of participants’ disposable income.

Educational and personal expenses of students are mostly taken care of by their families in Turkey. Depending on the families’ economic condition some students get larger and some get smaller amounts of allowance and some have to earn their own living. Therefore, the disposable income ranges from finite to infinite, which we assumed would constrain their choices and lead to differences in the degree of satisfaction with the use of money. High satisfaction will have facilitating and no satisfaction will have hindering effects in life, which consequently will have an impact on the values considered to be important, resulting in a difference of value-trait link between the high-income and low-income groups. We hypothesize that the value-trait link for the low-income group will be weaker than those of the high-income group.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants (595 in total) of the study include 462 (78%) undergraduate and 123 (21%) graduate students (and 10 -1%- missing response) from two state universities (32%) and from four private universities (68%) in Istanbul, Turkey. 348 (59%) females and 245 (41%) males (2 missing response) between the ages of 18 and 48 (M = 22.8, SD = 3.6), participated on voluntary bases and completed the questionnaires during class hours.

Instruments

Two scales were used for the measurement of value-trait link: Life Goal Values (LGV) questionnaire to measure values and Personality Profile Scale (PPS) to measure traits. Disposable income was measured by a single question.

Life-Goal Values

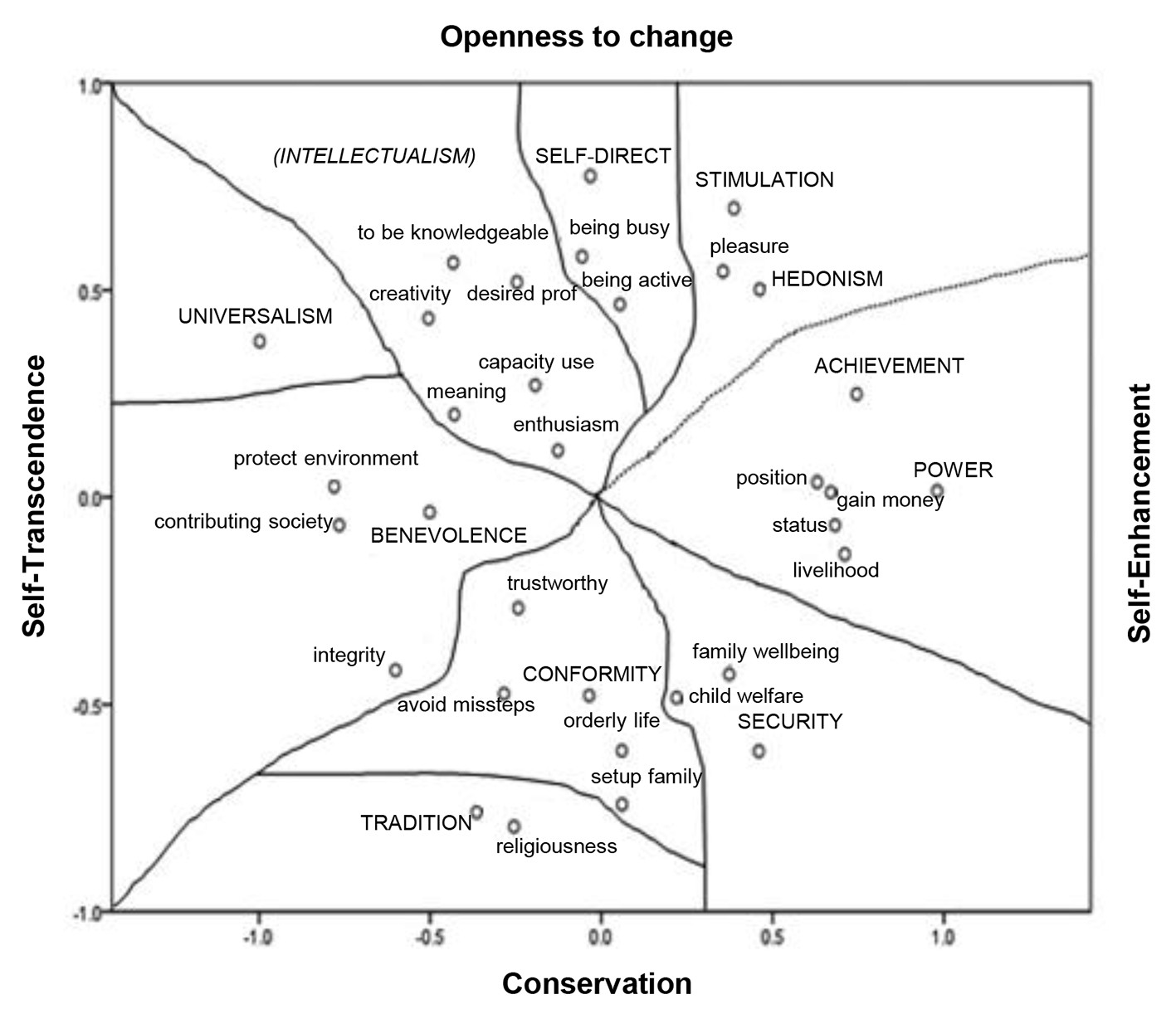

Values are measured with Life-Goal Values (LGV) questionnaire. It consists of 33 value items, 23 of which are indigenous items developed in Turkey and integrated with 10 PVQ itemsii, which was analyzed with multidimensional scaling proxscal (Tevrüz, Turgut, & Çinko, 2015). The 33 items were distributed to nine basic values. Conceptually similar indigenous and PVQ items joined together under the same regions as seen in Figure 1. However some adjacent but distinct values in Schwartz’s model formed single regions (e.g., stimulation/hedonism and achievement/power). There were no emic items corresponding to universalism, so it was represented with a single item transferred from PVQ. All the main values were given Schwartz’s universal value names except a specific ninth area, named intellectualism, which took place under openness to change region. Values of openness to change and self-enhancement on Figure 1 represent individual interest while values of self-transcendence and conservation represent social interest (Tevrüz et al., 2015). In the present study, participants were asked to answer the question, “How similar is this person to you?” Responses were given on a 6-point scale type with end points 1 (not a bit similar to me) and 6 (very much similar to me).

Figure 1

Configuration derived from the combination of WAG and PVQ items (Tevrüz, Turgut, & Çinko, 2015).

Personality Profile Scale (PPS)

For the measurement of personality traits, the 43-item PPS developed by Tevrüz and Türk Smith (1994) is used. PPS contains six factors detected with explorative factor analysis with principle component extraction method and labeled talent (outstanding, intelligent, superior, perfect, clever, talented and creative), agreeableness (docile, compliant, calm, silent, patient, self-sacrificing and modest), liveliness (cheerful, smiling, friendly, talkative, joking, funny and active), restlessness (distressed, pessimistic, nervous, impatient, conflicted and capricious), determination (determined, hardworking, ambitious and powerful) and selfishness (egoistical, selfish and aggressive). Gülgöz (2002) notices some resemblance between these factors and the Big Five model of personality traits. Talent and determination factors are compared with conscientiousness, which contains self-discipline, aim of achievement, dependable, organized tendencies. Agreeableness and selfishness (in low values) are similar to positive and negative poles of agreeableness of the Big Five, which reflects a tendency to be cooperative. Liveliness and restlessness matches with extraversion and neuroticism. However, Personality Profiles Scale does not cover the openness to experience dimension of the Big Five model. PPS is a product of a measurement in which the adjectives are evoked by everyday life experiences, not from lexical studies, which may incorporate infrequently used adjectives. Traits like imaginative, visionary, responsive and intuitive of openness/intellect dimension of the Big Five are rarely used adjectives in everyday discourse (Saucier, 1992). So this omission is expected.

The 43 items of PPS were inspected by a group of scholars and graduate students for up to datedness, and five items were eliminated due to changes in the meaning of items with time such as “yumuşak-soft” becoming to mean gay in current lexicon.

PPS is a self-rating bipolar scale, one of the poles representing similar to my personality ranging from 4 (very much) to 1 (very little) and the other pole contrary to my personality ranging from -4 (very much) to -1 (very little). Participants rate how much each adjective corresponds to or contradicts their personality on an 8-point bipolar scale.

Disposable Income

Participants’ disposable income was explored by a single questioniii, simply asking them to indicate the adequacy of their monetary status in spending money. Six response alternatives ranged from 1 (I can spend as much as I can, without giving much thought) to 6 (I can hardly meet even my basic necessities). Among these six response alternatives we name the first three measures as high income and the last three measures as low income. Since the aim of the present study is simply to compare the value-trait link of those who are financially well off and those who have financial difficulties in spending money, participants who selected one of the first three alternatives were grouped as having high income and participants who selected one of the last three alternatives were grouped as having low income.

Results

This section includes the analyses of higher-order dimensions of traits and values, value-trait relationships, the pattern of the value-trait relationships and the moderating effect of disposable income. But the PPS, which was developed 20 years ago, has not been used ever since. Furthermore, some items were eliminated for this study because of their change of meaning in 20 years, which made us suspect the original six-factor structure. So, for the present study we preferred to analyze the factor structure of PPS with explorative factor analysis and carry out further analyses stated above with the obtained structure. Hence we begin this section with the factor analysis of PPS.

Personality Profile Scale (PPS) Factors

Explorative factor analysis with principle component extraction method and obligue rotation for 38-item PPS extracted seven factors. Eight itemsiv are excluded from the analysis because of the low factor loadings. The results are given in Table 1.

Table 1

Factor Structure for Personality Profile Scale

| Factor Name | Items | Factor Loading | Factor Variance (%) | Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lively | 21.50 | .86 | ||

| 20 humorous | .82 | |||

| 34 playful | .80 | |||

| 24 cheerful | .76 | |||

| 15 smiling | .62 | |||

| 21 talkative | .59 | |||

| 06 friendly | .57 | |||

| 29 affectionate | .48 | |||

| Restless | 11.85 | .77 | ||

| 19 somber | .83 | |||

| 22 pessimistic | .81 | |||

| 31 distressed | .66 | |||

| 18 capricious | .62 | |||

| 09 conflicting | .53 | |||

| Competent | 7.19 | .78 | ||

| 41 capable | .85 | |||

| 40 creative | .83 | |||

| 43 intelligent | .76 | |||

| 01 clever | .59 | |||

| Agreeable | 9.06 | .74 | ||

| 26 peaceful | .83 | |||

| 28 quiet | .76 | |||

| 25 patient | .65 | |||

| 37 docile | .63 | |||

| Diligent | 4.89 | .72 | ||

| 04 determined | -.81 | |||

| 08 hardworking | -.77 | |||

| 16 ambitious | -.70 | |||

| Bold | 3.98 | .55 | ||

| 27 aggressive | -.73 | |||

| 32 nervous | -.61 | |||

| 07 daring | -.55 | |||

| Compassionate | 3.76 | .64 | ||

| 12 devoted | -.75 | |||

| 03 modest | -.62 | |||

| 05 selfish | .55 | |||

| 17 kind | -.47 | |||

| Total Factor Variance | 62.23 | |||

Note. Kaiser Meyer Olkin Sampling Adequacy = .84; Bartlett's Test of Sphericity Chi square: 9448.66; df = 435; p = .000.

Factors in Table 1 evoke the dimensions of the Big Five. For instance, adjectives, which locate on the first factor lively resemble the extroversion dimension of the Big Five facet, which includes adjectives, like active, sociable, talkative, etc. The second factor restless and the sixth factor bold have adjectives as in neuroticism of the Big Five expressing experiences of negative emotions. Combination of agreeable (Factor 3) and compassionate (Factor 7) bears a resemblance to agreeableness of the Big Five. Diligence (Factor 5) partly taps conscientiousness, which incorporates in the Big Five trait adjectives like hardworking, achievement-oriented and persevering. No correspondence to openness to experience/intellect is found in the indigenous Personality Profiles Scale. The only personality trait, which reminds openness/intellect of the Big Five, is “creative” of the competency factor. Lively has the highest reliability score (alpha = .86), whereas bold has the lowest (alpha = .56).

Higher-Order Dimensions of Traits and Values

In order to see the conceptual similarities between value and trait factors and keeping in mind the agentic and communion modalities, we ipsatized (centering within subjects) all values and traits, and applied a second order factor analysis (principle component with oblique) forcing values and traits to two factors. Table 2 gives the combined result of values and traits. There are five values and three traits in Factor 1. The traits (competent, lively, diligent) and four values (stimulation/hedonism, self-direction, achievement/power and intellectualism) are individual focused. In Bakan’s (1966, p. 14) terms they are “for the existence of an organism as an individual”. However, as the fifth value security of the social focused conservation dimension is also located in the same factor, but this is not anomalous, since security value shares the same motivational goal with power in avoiding or overcoming threats by controlling relationships and resources (Schwartz, 2012, p. 10). We can say Factor 1 is representative of the agentic modality. The second factor includes four values and two traits, which are social focused denoting relationship, social functioning; thus it is representative of the communion modality. However, this second factor is also related to the traits “bold” and “restless”. Bold implies an aggressive tendency and restless negative emotions. Both are negatively related to communion and have very low loadings. Because of the cognitive nature of values, these two traits of emotional content are not expected to have strong relations with values (Parks-Leduc et al., 2015).

Table 2

Second Order Factor Analysis for Value and Trait Factors

| Factor | Factor Loading |

|---|---|

| Factor 1: Agentic | |

| (V) Stimulation/Hedonism | .69 |

| (V) Self-direction | .66 |

| (V) Achievement/Power | .64 |

| (V) Intellectualism | .63 |

| (T) Competent | .57 |

| (T) Lively | .55 |

| (T) Diligent | .49 |

| (V) Security | .43 |

| Factor 2: Communion | |

| (T) Agreeable | .69 |

| (V) Conformity | .64 |

| (T) Compassionate | .60 |

| (V) Tradition | .56 |

| (V) Benevolence | .52 |

| (V) Universalism | .42 |

| (T) Bold | -.37 |

| (T) Restless | -.24 |

| Total Factor Variance | 36.44 |

Note. T = Traits; V = Values. Kaiser Meyer Olkin Sampling Adequacy = .72; Bartlett's Test of Sphericity Chi square = 2177.18; df = 120; p = .000.

Value-Trait Relations

The value-trait relation was analyzed with univariate regressions of values on traits (forward inclusion). Results are given in Table 3. All personality traits, even restless, have significant links with values, but R2 values (ranging from .09 to .19) demonstrate low contributions to variance. The strongest links are between compassionate and conformity (ß = .33), between compassionate and benevolence (ß = .31) and between lively and stimulation/hedonism (ß = .30). Remaining links vary between ß = -.09 and ß = .26.

Table 3

Regression Analysis of Nine Value Factors on Seven Traits

| Statistic | Self-Enhancement

|

Self-Transcendence

|

Conservation

|

Openness to change

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ach/Power | Benevolence | Universalism | Security | Conformity | Tradition | Intellectualism | Self-direction | Stim/Hedo | |

| R2 | .17 | .19 | .10 | .09 | .16 | .11 | .18 | .09 | .14 |

| F value | 19.86*** | 28.75*** | 14.55*** | 12.67*** | 24.25*** | 21.59*** | 21.79*** | 16.68*** | 26.93*** |

| Trait | ß value | ||||||||

| Lively | .19*** | -.10* | .10* | .15*** | .30*** | ||||

| Restless | .11* | .13** | |||||||

| Competent | .11* | .11* | -.10* | .20*** | .15*** | .12** | |||

| Agreeable | .09* | .12** | .10* | .14** | -.09* | ||||

| Diligent | .19*** | .11* | -.14** | .19*** | .13** | .23*** | |||

| Compassionate | .31*** | .26*** | .11* | .33*** | .25*** | .16*** | .10* | ||

| Bold | .10* | -.11* | .13** | -.10* | |||||

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Based on two major findings of the meta-analytic studies (Fischer & Boer, 2015; Parks-Leduc et al., 2015), regression results given in Table 3 are inspected on two grounds: 1) whether the nature of trait-value links are similar to earlier meta-analytic studies, and 2) whether link patterns are in accordance with value structure, in which case traits having links with values of one pole should not have links with values of the opposite pole, too.

Value-Trait Links of Openness to Change and Conservation Values

Values on the openness to change dimension emphasize individual interest and are cognitive in nature, revealing individual control and accomplishment. The three values given on Figure 1 for openness to change are intellectualism, self-direction and stimulation/hedonism. Intellectualism is about meaning, enthusiasm and capacity use. Self-direction is about independent thought and action, exploring and creating. Both are linked to competent (ß = .20 and ß = .15 respectively) (Table 3). Intellectualism is also related to diligent (ß = .23) described as determined, hardworking and ambitious (Table 1). Self-direction and stimulation/hedonism, on the other hand, have links with lively (ß = .15 and ß = .30 respectively). These three personality traits (competent, diligent and lively) are directed to individual interest and they have a cognitive nature like the basic values to which they are linked in the agentic modality (Table 2). However, intellectualism is related also to compassionate (ß = .16), which has a social and emotional content described as devoted, modest and kind (Table 1), hence its negative relation with bold (ß = -.10) is rather spontaneous.

Conservation pole -opposite of openness to change pole- includes security, conformity and tradition values. They represent collective interest and are about safety for children and family, compliance to social norms by having an orderly life, being trustworthy, avoiding missteps and acceptance of and respect for tradition and religion (Figure 1). Conformity and tradition are linked to agreeable (ß = .10 and ß = .14 respectively) which includes peaceful, quiet, docile and patient personality traits (Table 1) sharing the communion modality with these values (Table 2). Like security they are also related to compassionate (ß = .11, ß = .33 and ß = .25 respectively), which implies social interest (Table 1). These traits are conceptually fitting to the conservation dimension. Also the negative link between conformity and competency -a trait of the opposite pole- (ß = -.10) is in accordance with the structural pattern of the value theory.

However, conformity and security values are also related to diligent (ß = .13, ß = .19), and security to lively (ß = .10). While tradition gets in relation with bold (ß = .13), those who give importance to security seem to reject boldness as a personality trait (ß = -.11). The two traits (lively and diligent) have individual focus and agentic meaning, which is more appropriate to openness to change values of the opposite pole. So, all value types of conservation share traits of the opposite pole values, which contradict to the structural pattern of the value theory and the results of the two meta-analytic studies (Fischer & Boer, 2015; Parks-Leduc et al., 2015). However, this sharing is acceptable with the agentic-communion model (Wiggins, 1991).

Trait-Value Links of Self-Transcendence and Self-Enhancement Values

The second higher order value dimension is self-enhancement of individual interest versus self-transcendence of collective interest. Achievement and power of the self-enhancement pole, which exist as independent value types in Schwartz’s value model, are united as a single value in a previous study (Tevrüz et al., 2015) and are analyzed as a single value in the present study, too. Regression analysis with forward inclusion gave relevant links between achievement/power and personality traits, which symbolize individual interest (lively: ß = .19, competent: ß = .11 and diligent: ß = .19). However, restless and bold which have negative emotional connotations are also related to achievement/power (ß = .11, ß = .10 respectively).

Benevolence and universalism are self-transcendence values at the opposite pole, assessing social interest. They have links with agreeable (ß = .09 and ß = .12, respectively). The two meta-analyses also gave the same relation (Fischer & Boer, 2015; Parks-Leduc et al., 2015). Likewise compassionate, the second trait of social interest, also relates with benevolence and universalism (ß = .31 and ß = .26, respectively). Benevolence also gets in relation with traits signifying individual interest. Benevolence is represented by welfare of others, integrity, contribution to society and protection of the environment (Figure 1). Being competent (ß = .11) and diligent (ß = .11) seem to be functional for those who give importance to benevolence. On the other hand, being lively and diligent seem to be contrary to universalism (ß = -.10 and ß = -.14), which was represented by the wording “equality for all”.

Pattern of the Value-Trait Relations

Schwartz’s value theory states that an outside variable related to a value is similarly related with the adjacent values and the relation gets weaker as the value type departs from the most positively related value. Schwartz (1996), Morselli, Spini, and Devos (2012) and Parks-Leduc et al. (2015) supported this pattern.

Traits and values of the same modalities share the same factor (Table 2), but regression analysis shows that some values are also related to the traits of the opposite modality (Table 3) and this relation is not in accordance with values’ structure, but is acceptable with the agentic and communion framework.

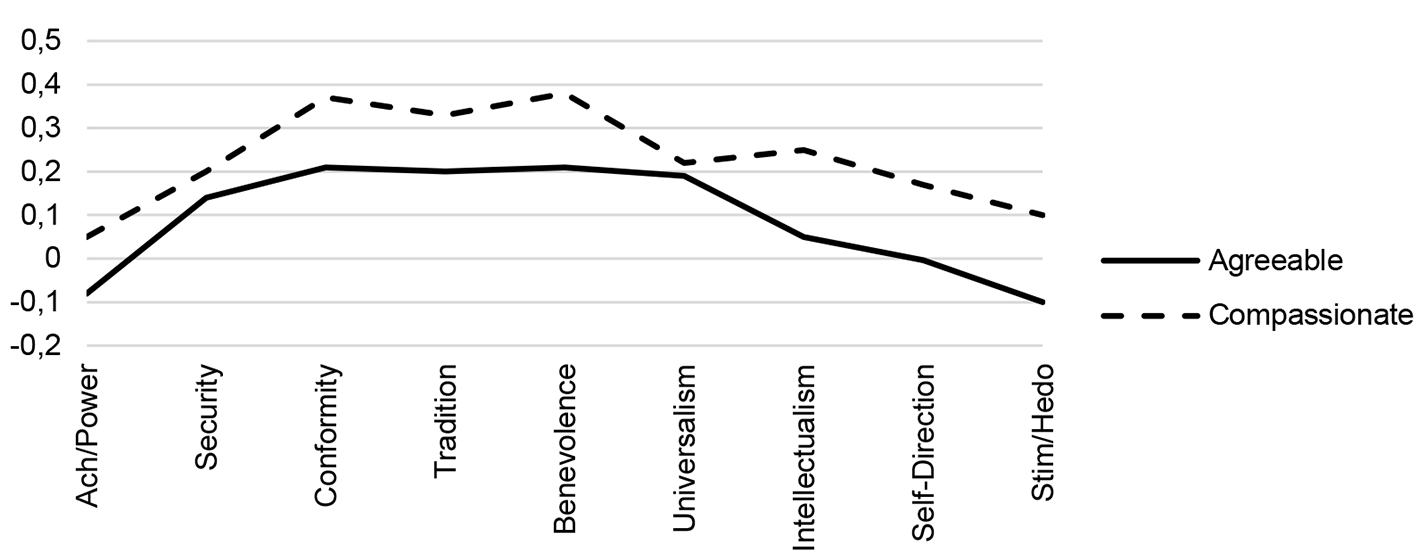

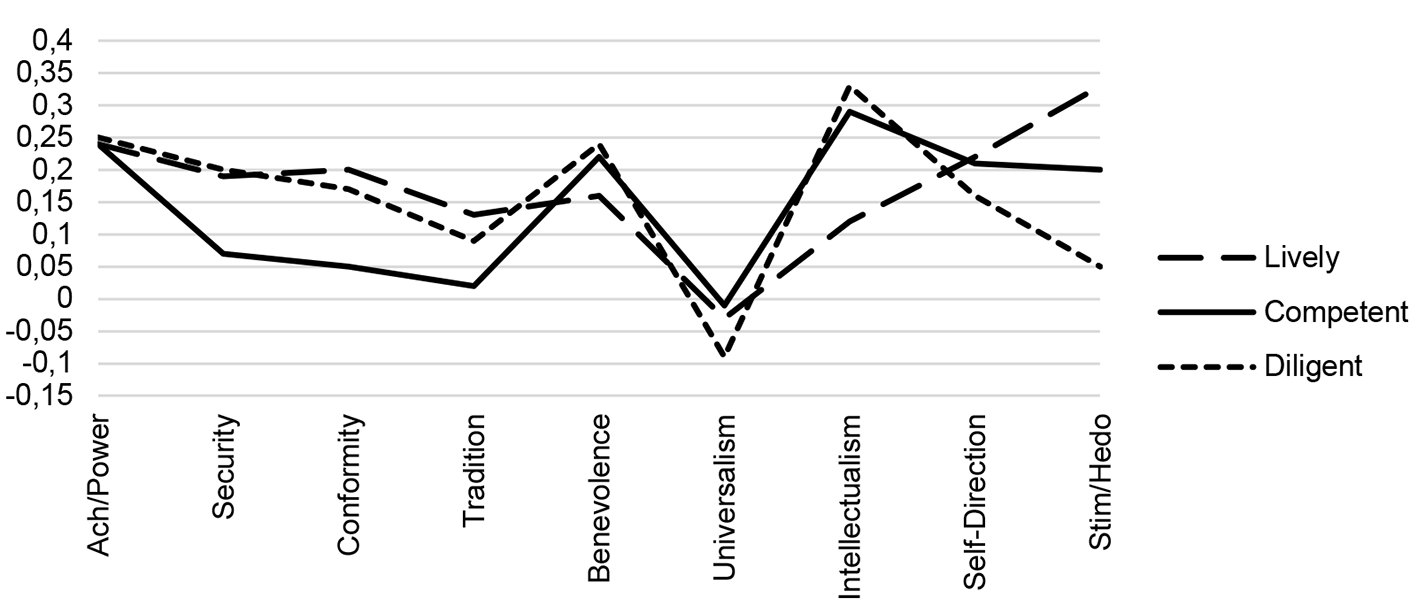

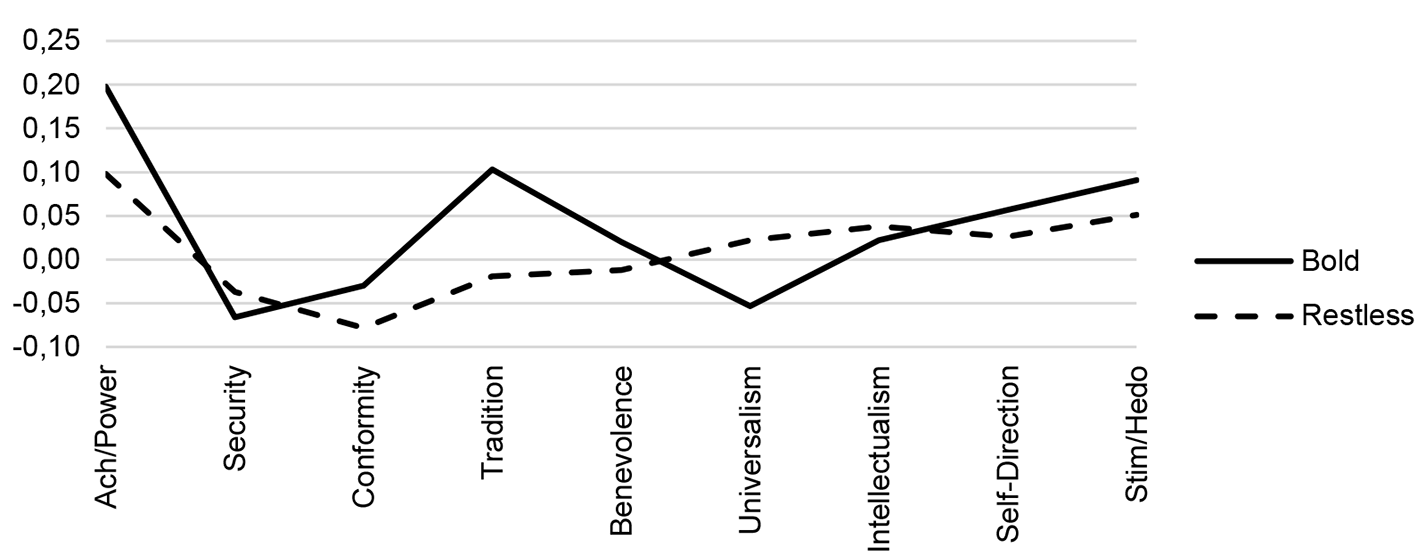

In order to see the pattern of value-trait relations, correlations between traits and values are graphically represented as advised by Schwartz (1992, 1996). The values are placed on the horizontal axis in the order they take on the value circle given in Figure 1 and the traits in three separate groups (communion traits, agentic traits and traits having negative emotion) are plotted on the vertical axis. We used Pearson correlation coefficients between values and traits (Figure 2, 3 and 4Figure 3Figure 4).

Figure 2

Results for social tendency traits (agreeable and compassionate).

Figure 3

Results for individual tendency traits (lively, competent and diligent).

Figure 4

Results for negative emotional tendency traits (bold and restless).

Figure 2 gives the sinusoid pattern as predicted by the value theory (Schwartz, 1996). Higher correlation of agreeable and compassionate with the adjacent conservation and transcendence values gets weaker in both directions. Figure 3 of individual focused agentic traits (lively, competent and diligent) gives a different picture, especially with competent and diligent traits. The two peaks with achievement/power and intellectualism, which are individual-focused agentic values, is expected, but the third peak with benevolence of social-focused communion value distorts the pattern. Competence and diligence seem to be functional for benevolence. On the other hand, lively demonstrates a more accurate pattern predicted by the value theory.

The pattern of restless is also fitting to the prediction (Figure 4). A positive correlation of restless with achievement/power and the adjacent stimulation/hedonism values also get weaker as values move away from achievement/power. But such a pattern does not hold for bold. The trait bold shows a deviation by its positive relation with the value tradition.

The pattern and regression results obtained in the present study show that especially values of communion get in significant relations with agentic traits, which is not in accordance with values’ structure. However, when approached as agentic-communion entities, they facilitate or mitigate each other (Abele & Wojciszke, 2014, p. 9). On the whole, although the development of the items of the two instruments used in this study was of indigenous nature, results of value-trait relations measured with these instruments are relatively comparable with those achieved by the universal instruments.

Disposable Income and Value-Trait Relationships

Fischer and Boer (2015) found a moderating effect of restricting conditions on the strength of value-trait relations. In the present study disposable income is hypothesized as having a moderating effect on the value-trait link. It is coded as a dummy variable and is multiplied with personality traits to be entered as a third predictor into the regression analysis. However, the high correlation of this predictor variable with the dummy variable led to multicollinearity problem. Hence, correlation analysis is applied for the value-trait links of high-income and low-income groups, and Fisher’s Z is calculated for the significance of difference between correlations (Preacher, 2002; SAS Institute, Inc., 2010).

The two groups differ on five value-trait relations (Table 4). Value-trait links are stronger for the high-income group, supporting earlier findings on the country level (Fischer & Boer, 2015), except for achievement/power-bold and achievement/power-diligent relation (Z = -2.59, 95% CI [-.40, -.06] and Z = -3.08, 95% CI [-.44, -.10]). Bold people (defined as aggressive, nervous, daring) and diligent people (defined as determined, hardworking, ambitious) give importance to achievement and power more when they have low income. But when the income is high, diligent people give importance to intellectualism more (Z = 2.05, 95% CI [.0002, .34]).

Table 4

Difference Between High-Income and Low-Income Groups

| Trait, Value | H

|

L

|

Fisher’s Z | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | n | r | n | |||

| Competent | ||||||

| Benevolence | .33*** | 266 | .14** | 272 | 2.27* | [.03, .37] |

| Diligent | ||||||

| Achievement/Power | .14** | 259 | .39*** | 275 | -3.08*** | [-.44, -.10] |

| Intellectualism | .42*** | 261 | .27*** | 273 | 2.05* | [.0002, .34] |

| Bold | ||||||

| Achievement/Power | .09 | 263 | .31*** | 276 | -2.59** | [-.40, -.06] |

| Compassionate | ||||||

| Stimulation/Hedonism | .21*** | 267 | .03 | 277 | 2.11* | [.01, .35] |

Note. Only significant relations are reported. H = High income; L = Low income.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

The other two traits related with values are competent and compassionate. Competent is individual-focused, but is linked to the social-focused benevolence value when income is high (Z = 2.27, 95% CI [.03, .37]). Those who don’t have difficulty in spending money are more open to benevolence if they are competent. It is interesting to note that when income is high, those who are compassionate give also importance to stimulation and hedonism more (Z = 2.11, 95% CI [.01, .35]). Relation between compassionate (devoted, modest and kind) and stimulation/hedonism (fun, exciting life and pleasure) does not seem to be in tune, but as seen from Table 3, one of the highest contribution to stimulation/hedonism comes from liveliness (ß = .30), which encompasses traits of affection like friendly, smiling, affectionate. However, further exploration for clarification is needed.

Discussion

Studies done on value-trait links with universal scales provide some meaningful relationships (Fischer & Boer, 2015; Parks-Leduc et al., 2015). Also, the values and traits of these scales are found to be differentiated to agentic and communion constructs, which are considered as two fundamental modalities of human existence (Paulhus & Trapnell, 2008; Trapnell & Paulhus, 2012). This study looks for conceptual similarities of indigenous value-trait relationships with those found with universal measures and with the two fundamental modalities. Moderating effect of disposable income on value-trait relationships is also inspected. We first discuss the comparable and incomparable findings and then the moderating effect of disposable income.

Comparable Findings

Indigenous value items stem from Turkish people’s responses given to work goal and achievement goal questions which integrate with Schwartz’s values (Tevrüz et al., 2015). Likewise, the indigenous personality trait items resemble the Big Five trait items although the items are derived from Turkish people’s self-descriptive responses. Hence, in terms of resemblance of indigenous scales to near universal scales, we evidence some conceptual similarities, which we expect to be repeated in the value-trait relationships and in their decomposition to agentic-communion constructs.

As for the value-trait relationships, the meta-analytic studies report that, one of the most consistent value-trait relationship holds between the trait agreeableness and the value benevolence. Agreeableness also seems to have a moderate relationship with universalism, conformity and tradition (Fischer & Boer, 2015; Parks-Leduc et al., 2015). The present study replicates these findings.

The other most consistent relationship is between openness to experience trait and openness to change (especially with self-direction) value. Openness to experience factor of the Big Five is a broad trait having the most cognizant and individual focused features. The indigenous Personality Profile Scale does not have the richness of this broad factor, but the factor competent (with traits such as capable, creative, intelligent and clever) has a cognitive nature with an individual focus and its relation with intellectualism and self-direction, which are also individual focused, is analogous to openness to experience and openness to change relation. So far, these relationships derived through indigenous and near-universal scales seem to be in conceptual agreement.

Meanwhile, the two fundamental modalities, agentic and communion concepts, set up a framework for distinguishing two aspects of values and traits (Trapnell & Paulhus, 2012). Agentic refers to goal achievement and task functioning, whereas communion refers to maintenance of relationship and social functioning (Abele & Wojciszke, 2014). Findings of the present study give a similar conceptual decomposition of indigenous values and traits to two fundamental modalities, which are nearly perfect representatives of agentic and communion constructs (Table 2). Security, as a conservation value seems like an outsider to agency. However security is an adjacent value to power (an agentic value), and they both stress the “same orientation on the motivational continuum around the circular value structure” (Schwartz, 1996, p. 124); so, its existence does not distort the agentic picture.

Incomparable Findings

Table 3 gives some opposing values, which share the same personality traits; that is, some agentic values are associated with communion traits (like intellectualism and self-direction with compassionate), and some communion values with agentic traits (like conformity, and benevolence with diligent and competent). In each case the conflicting value poles are similarly associated with some of the traits and this is incompatible to the theorized value structure (Roccas et al., 2002; Schwartz, 1992, 1996). On the other hand, it is compatible with the explanations of the two fundamental modalities of human existence. It is quite possible that the content, nature and the assigned meaning of the outside variable (the traits) function as agency and communion attributes in corroborating the values of opposite poles. This brings to mind the possibility that communion (or agentic) values may be in conjunction with agentic (or communion) traits if these traits do not contradict each other. For example, a person, who gives importance to intellectual values may also have compassionate tendencies for others as well as being competent and diligent for herself; or a person, who gives importance to conformity, may well be a diligent person as well as being compassionate and agreeable. A person, who gives importance to benevolence, may also need to be a competent and a diligent person besides being agreeable and compassionate; or a person maybe lively, diligent and also compassionate for keeping close others from difficulties or hardship. Such results are expected in the agentic and communion conceptualization, since they are two fundamental modalities in the existence of individuals (Bakan, 1966, pp. 14-15). Individuals exhibit their broad classes of behavior in a social environment, where they act as participants (communion); they also exist for their own goals and aspirations (agency). Abele and Wojciszke (2014, p. 9) resemble them to the dual nature of human existence. They are not independent; they mitigate each other. If they don’t, for example; if an extreme form of dominance (agency) is not mitigated with kindness (communion) it will be harmful both for the self and for interacting others. Moreover, a study (Abele, 2014) done on life satisfaction found that the highest satisfaction occurred when communion-values were moderated by agentic-traits. The value-trait relationships attained with the indigenous instruments used in this study are in coherence with the dual perspective model of agency-communion.

The theorized value pattern of Schwartz’s model proposing the opposition of the value poles, especially when they are associated with outside variables, seems to call for integration with the agency-communion model. Under what conditions and with which constructs corroboration between opposing values occur seems to be a challenging research question. Furthermore, it would enrich our understanding of values and also individuals if we know what it means to make or not to make distinctions between opposite poles.

Financially Advantaged and Disadvantaged Groups

Fischer and Boer (2015) hypothesized and found that under threatening conditions value-trait relationships get weak. The results of this study show weak relationships between values and traits. Those, who have financial difficulties show weaker links especially with openness to change values (intellectualism and stimulation/hedonism) and benevolence, but the relationship of bold and diligent with achievement/power is stronger. Diligence and boldness seem to be functional for the financially disadvantaged to attain achievement/power. Diligence, with its hardworking, determined and ambitious features, is a reasonable and useful instrument for attaining achievement/power, but the instrumentality of boldness is rather doubtful. When comparisons are made, the financially disadvantaged group may perceive own status as a state of injustice, which stimulates anger and aggression (Adams, 1965; Brown, 1986), and bold bears aggressive, nervous and daring features. These descriptions of bold bring to mind the Dark Triad, which is composed of Machiavellianism, narcissism and psychopathy, which are malevolent and antisocial traits in general population, and all three traits are significantly correlated with power and achievement (Kajonius, Persson, & Jonason, 2015). Lack of the Dark Triad trait measurement seems to create weaknesses in personality traits and value studies. With the use of these traits we could have obtained more information about “financially disadvantaged-bold” relation as well as about “tradition-bold” relation.

Conclusion

As a conclusion, we can say that the relationships between personality traits and values measured with near universal and indigenous instruments present conceptual similarities, supported by the agentic-communion dual perspective. The present study contributes to the literature by demonstrating the plausibility of value-trait measurement with a new (indigenous) set of traits and values, which give comparable results to those obtained with near universal measures. On the other hand, the incomparable findings demonstrate the potential of emic measurements exposing some unpredicted findings, which we think should be taken into consideration in values research, especially when relationships with an outside variable and the effect of a moderator is studied. Inclusion of the two fundamental modalities into the values studies would give new insights.

We think the adopted emic approach may serve to encourage the development of novel instruments with an emic approach, which may help to expose cultural and transcultural trends. Besides, we can say that the findings of this study gave us the opportunity to see Turkish university students’ description of values in terms of their self-understanding. It would be interesting to follow up and see if their values and self-descriptions change in Turkey, where the government gets increasingly authoritarian and pan-Islamic, demonstrating malevolent practices on environmental and judicial issues and where there is a continuous increase in unemployment-rates (Gökay & Xypolia, 2013; http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/PreIstatistikTablo.do?istab_id=2262).

Limitations

The generalizability of the findings of the study is not so wide as including Turkish people as a whole, since the sample consists of only students of Universities settled in Istanbul. For example, because of the characteristics of the sample, intellectualism value may be specific only to students in the academic life; and the relationship of restless and diligent traits with intellectualism may be more a characteristic of young people. Hence, replication is needed with future studies, which have diversities in age, education and home city (urban or rural).

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (