In recent years, stalking has increasingly been recognised as a social and legal problem and has captured the community’s and media’s interest. The term “stalking” emerged in the early nineties in the Anglo-Saxon countries, following some incidents of persecution that involved public personalities from the entertainment world. Subsequently, this phenomenon has rapidly increased also in the general population (De Fazio & Sgarbi, 2009), mainly as product of a growing culture which seems to reveal the crisis of current rules of social coexistence.

According to data from the National Observatory for Stalking (ONS) (2009), 20% of the Italian population was a victim of stalking, mostly females, 17% out of the total reported it and in 90% of the cases there was a previous relationship between victim and stalker. More precisely, stalking occurred in 55% of cases within couples, in 25% between neighbours, in 15% at work and in 5% within the family (children, brothers/sisters and parents). According to research conducted in Italy by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) (2007), 2 million and 77 thousand women suffered stalking by ex-partners, equal to 18.8% of the divorced/separated Italian women, and 48.8% of them were subject to persecutory behaviours (such as unwanted communication, shadowing, threats) before being victim of physical or sexual violence.

With regard to this emergency, the Decree-Law 11/09 was finally approved in Italy; this introduced the new offense of stalking into the penal code (Law no 38 of 23 April, 2009). However, despite the growing attention to the issue and the extensive literature produced in recent years, several limitations are found in coming to a clear definition of the phenomenon. Consider, for example, the difficulty of scientifically defining and measuring harassing behaviours because of the simultaneous coexistence of normal behaviour and threatening acts that potentially have both clinical and legal consequences (Centro documentazione donna di Modena, 2010). This difficulty mainly relies on the fact that the stalking definition is often based on the perception of intrusiveness of such behaviour, depending on the victim’s tolerance and reactivity level. Indeed, the legal definition of stalking in Italy refers to persecutory acts done repeatedly which make the victims experience a serious and continuing state of apprehension and fear for their safety or that of any other person close to the victim and which compel victims to alter their own choices or life habits. In this sense, the offence of stalking deals with both an objective and subjective standard of harm because the offender must intend to cause harm or apprehension and the victim must subjectively experience such an affect. This makes the stalking detection quite complex because the subjective intent of a person can be difficult to prove, as well as the victim’s experience and distress, thus requiring the competence to analyse interpersonal behaviours within a relational perspective.

Current classifications of stalking thus depend not only on the characteristics of what is classified, but also on the needs of their proponents (Curci, Galeazzi, & Secchi, 2003). The classifications drawn up by several groups (clinical professionals, lawyers, etc.) emphasise their specific objectives and are consistent with their assumptions and languages. Indeed, to date, several classification systems have achieved some popularity, since no single system has been firmly established in the literature on the issue. As stated by Canter and Ioannou (2004, p. 114):

“Different explanations and their related typologies are derived for different reasons, for example in an attempt to predict dangerousness or to offer aetiologies or to provide guidance to the courts on appropriate sentencing, but this diversity creates a lack of clarity in modelling the actions of stalkers. The mixture of sources of information from which the classifications are derived also adds to this confusion”.

Theoretical Framework

Despite the heterogeneity of its manifestations, stalking is generally defined as a set of repetitive and intrusive behaviours regarding surveillance and control, search for contact and communication, that are unwanted by the victim that perceives them as arousing concern and fear (De Fazio & Galeazzi, 2005). In this regard, some authors proposed a definition of stalking syndrome (Galeazzi & Curci, 2001) including three types of behaviour: unwanted communication, unwanted contact and associated behaviours. Unwanted communication deals with letters, phone calls, text messages, e-mails which, usually, are directly addressed to the victim, but may also consist of threats to the victim’s family, friends or colleagues. Unwanted contact refers to behaviours that aim at approaching and getting close to the victim in some way, such as shadowing. Finally, associated behaviours can range from sending unwanted gifts or floral tributes, to threats and property damage, physical aggression and violence. Meloy and Gothard (1995) utilise the term “obsessional follower” to describe the individual who persecutes or harasses another person. However, what allows us to define stalking, is not the repetition and persistence of certain controlling behaviours over time, but rather the subjective threat perceived by the victim, who finds such behaviours intrusive and unwelcome (Mullen, Pathé, & Purcell, 2009).

As well as research on forensic and legislative interventions (Caldaroni, 2009; Forum-Associazione Donne Giuriste, 2009), several studies were also developed in clinical setting with regard to the different types of abuser-persecutor’s behaviour (Mullen, Pathé, & Purcell, 2009; Mullen, Pathé, Purcell, & Stuart, 1999; Wright et al., 1996; Zona, Sharma, & Lane, 1993), psychological impact of stalking on victims (Pathé & Mullen, 1997) and therapeutic measures promoting both the victim’s recovery and the stalker’s recovery (Rosenfeld et al., 2007; Warren, MacKenzie, Mullen, & Ogloff, 2005).

Most of the existing literature on the subject is therefore limited to the legal and psychiatric issues, in accordance with mainstream scientific research that has focused primarily on the criminological and social health field. Indeed, these two approaches aim at detecting some criteria which consent to define stalking, mostly seen as deviance from the norm. Legal measures are hypothesised to be a good deterrent to stalking, while clinical research is regarded as useful in providing objective indicators for diagnosis and prevention. However, to date, it emerges that legislative interventions are quite ineffective in reducing this phenomenon (Modena Group on Stalking, 2007). In addition, it is not possible to establish a direct relationship between stalking and psychiatric or clinical disorders (Gargiullo & Damiani, 2008; Marasco & Zenobi, 2003). This highlights the profound limits of the rationalist postulate, shaping the legal perspective which looks at the individual as rationally oriented to follow social norms, and of the individualistic postulate, mostly taken in clinical research, according to which behaviour is apart from the context and characterised by inner psychological processes (Grasso & Salvatore, 1997).

In this paper, we aim to develop a contextualistic psychological perspective on stalking which overcomes both these postulates based on the split between emotionality and rationality on the one hand, and on the split between individual and context on the other. In order to better understand the subjective component of stalking, the focus has to be moved from a behavioural framework to a socio-constructivist one, which allows the exploration of representations that seem to shape this phenomenon. Indeed, human behaviour is regulated not only by cognitive and rational dimensions but also by motivational and emotional dynamics which can affect social relationships, as well as social norms. Besides, individual-centred theories share the assumption that the mind (in a broad sense) is contained in people’s heads. Such theories do not necessarily deny the importance of relational dynamics and the role of the context. They however attribute structural autonomy to the intrapsychic apparatus and consequently take the individual as the unit of observation. Conversely, contextualistic theories do not necessarily reject the intrapsychic; however they consider the intrapsychic dimension to be non-autonomous, but part of a social process that is organised in an environment that includes but also transcends the individual.

The Present Study

This paper aims to explore the cultural models which organise the stalking discourse from a content analysis of Italian newspapers. By “cultural models” we mean the collusive dynamics, in terms of shared emotional and symbolic components, through which people represent a specific topic or “object” of investigation (Carli & Paniccia, 2002), in our case stalking. In this perspective, the construct of “collusion” refers to the emotional sharing of affective symbolisations of objects within a context and represents the link between individual models and cultural systems of social coexistence. By social coexistence we mean the symbolic component of human relationships based on shared rules which allows people to exchange and live together. Indeed, cultural models do not specifically deal with common sense, in terms of cognitive evaluations, beliefs or stereotypes; rather they include affective meanings which people attribute to reality or social events, and symbolic processes which regulate interpersonal relationships. In this sense, cultural models shape social representations because affective symbolisations that people experience in daily interaction and communication consent to enhance consensus and stability in representations among individuals participating within the same context. The sharing of emotional symbols, which may be either the same or complementary, allows them to relate to each other in a way that mutually satisfies their needs.

The adoption of a socio-cultural approach, based on an individual-context paradigm (Carli, 1990), may allow us to overcome the individualistic and medicalised perspective currently proposed by mainstream research, which mostly aims at detecting the boundary between normality and pathology in the definition of stalking. According to this framework, the social and the individual, the cognitive and the cultural, mind and society constitute functional units and social representations are manifested in any social practice. Individuals are socially located and acquire their beliefs about stalking from the discourses and constructions that are available to them. In this sense, media representations of stalking produce and reproduce meaning concerning this phenomenon, for lay people and professionals alike, and mediate individuals’ lived experiences. It is thus possible to explore collective meanings related to our object of investigation, without assuming a normative and well-defined stalking definition or testing specific hypotheses previously assumed by the researcher. The adoption of a socio-cultural approach allows the contextualisation of stalking and the detection of specific collective dynamics which seem to be associated with the risk of stalking situations. This could help institutional agencies to develop attitude change in stalking prevention by making interventions more reflective of local socio-cultural conditions and hence more effective.

In detail, we refer to Moscovici’s theory of social representations (SRT) (Moscovici, 1988, 2005) according to which meaning is created through a system of social negotiation from discursive productions, rather than being a fixed and defined thing. In this sense, mass media (newspapers, radio and television) have a fundamental role in the formation and communication of social representations through the rapid communication of ideas and images, because commonsense knowledge is directly related to how people interpret or translate the knowledge that is socially transmitted by means of public information system (Sommer, 1998). According to Moscovici (1973):

“A social representation is a system of values, ideas and practices with a twofold function: first, to establish an order which will enable individuals to orientate themselves in their material and social world and to master it; and secondly to enable communication to take place among members of a community by providing them with a code for social exchange and a code for naming and classifying unambiguously the various aspects of their world and their individual group history” (p. xiii).

In this sense, SRT can give valuable contributions to media research. Indeed, by studying how the media and the public anchor and objectify “new” scientific, political and social issues, we obtain knowledge about vital transformations in the thought-systems or collective meaning-making of societies, because ongoing changes are not only structural material processes but also deeply emotional.

In this regard, the analysis of press is meant to reveal the main processes by which media language contributes to the construction of social representations of stalking: processes of anchoring and objectification (Moscovici, 2000). Anchoring involves the ascribing of meaning to new phenomena by means of integrating it into existing worldviews, so it can be interpreted and compared to the "already known". By naming something, “we extricate it from a disturbing anonymity to endow it with a genealogy and to include it in a complex of specific words, to locate it, in fact, in the identity matrix of our culture” (Moscovici, 2000, p. 46). Objectification is a mechanism by which socially represented knowledge attains its specific form. It means to construct an icon, metaphor or trope which comes to stand for the new phenomenon or idea. It has an image structure that visibly reproduces a complex of ideas (Lorenzi-Cioldi, 1997; Moscovici, 1984, p. 38). Sometimes called the ‘‘figurative nucleus’’ of a representation, an objectification, captures the essence of the phenomenon, makes it intelligible for people and weaves it into the fabric of the group’s common sense.

Information originating from the mass media plays a central role in SRT. Few members of the public have individual access to knowledge about scientific advances, for example, except through the mass media (Moscovici & Hewstone, 1983), so it is natural that a study of social representations generally begins with an explication of the content and nature of information being disseminated through the media. As Gaskell (2001) pointed out, when a new phenomenon arises, people do not simply sit alone to wonder about the nature of the phenomenon and what it might mean to them or the communities to which they belong. The majority of people will first rely on the media for information and then turn to conversations with family and acquaintances (Gaskell, 2001; Southwell & Torres, 2006). As suggested by Moscovici (1998), once a social representation is formed, its power will actually supersede individuals’ own direct experience with a phenomenon, because media contents serve as a proxy for direct experience and may have the same cognitive and emotional force as direct experience (Joffe, 2003). At the same time, a social representation allows us to account for the potential effectiveness of the discursive moves that emerge from the co-constitutive relationship between contexts and communicative practices. Indeed, discursive practices do not merely reflect an already existing social reality, but they also helps to create that reality, because meanings and representations are dynamically co-constructed by individuals, from their particular social interactions.

The analysis of stalking discourse within newspapers could thus provide a portrait of public knowledge and image regarding this phenomenon.

Method

Newspapers and Collection of Articles

For the research it was decided to consult Italian newspaper articles produced over five years (between 1st January, 2006 and 31st December, 2010) using the archives of the main three national newspapers: La Repubblica, Corriere della Sera and La Stampa. The research was carried out by inserting the word “stalk*” in the search engines of the three newspapers, which retrieved all the articles containing the word in the body of the article or in the headline. A careful reading allowed us to select only the articles focusing on the topic, discarding those in which “stalk*” was only mentioned or in which the word was just listed, or used in a metaphorical sense. The result was a sample of 496 newspapers articles (263 from La Repubblica, 123 from La Stampa and 110 from Corriere della Sera).

Emotional Text Analysis

Emotional Text Analysis (AET) (Carli & Paniccia, 2002) is a psychological tool for the analysis of written texts that allows the exploration of specific cultural models structuring the text itself, thus outlining the “emotional construction of knowledge” of a certain research object, in our case stalking. According to this methodology, emotions are not considered as individual responses but as shared categorisation processes by which people symbolise the reality and are expressed through language, something which is consistent with the theory of social representations.

Specifically, AET allows to get a representation of textual corpus contents through few and significant thematic domains. It does not derive the internal structure of a corpus from ad hoc categories established by the researcher, but rather from the distribution of the words in the corpus itself, because the sense of a text can be represented in terms of its semantic variability. Analysis results can be considered as an isotopy (iso = same; topoi = places) map where each of them, as generic or specific theme, is characterised by the co-occurrences of semantic traits. Isotopy refers to a meaning conception as a "contextual effect", that is something that does not belong to words considered one by one, but as a result of their relationships within texts or speeches. The isotopies function help in understanding speeches (or texts); in fact, each of the isotopies detects a reference context shared among a number of words, which however does not result from their specific meanings. That is because the whole is something different from the summation of its parts. Isotopy detection, therefore, is not a simple “fact” observation, but the result of an interpretation process. As Hall (1997) argued, these “maps of meaning” reflect cultural models as frameworks for classifying the world according to some hierarchical value system and for ordering people’s lives.

As Gee (2001) noted:

“Cultural models tell people what is typical or normal from the perspective of a particular discourse… [they] come out of and, in turn, inform the social practices in which people of a discourse engage. Cultural models are stored in people’s minds (by no means always consciously), though they are supplemented and instantiated in the objects, texts, and practices that are part and parcel of the discourse” (p. 720).

By cultural model we mean a motivational framework for representations that are intersubjectively shared by a social group within a specific context. According to AET, language does not only refer to individuals’ cognitive meanings, but it also expresses the emotional experience which mediates social interactions, as well as practices that are culturally accepted. For instance, the cultural models of immigration do not exclusively account for the public image of the phenomenon; rather they deal with the collusive dynamics, such as affiliation, power or fear, regulating a wide range of aspects within a social system (i.e., school inclusion, labour market access, anti-racism policy, etc.).

The basic hypothesis of AET relies on the “double reference” principle - both lexical and symbolic - implicitly connected to the language text (Fornari, 1979). This allows one to capture the emotional and symbolic dimensions running through the text, apart from its intentional structuring or cognitive sense. In this sense, with polysemy, we refer to the infinitive association of emotional meanings attributable to a word, when it is taken out of language context. Thus the words organising the language sample can be divided into two large categories: dense words, with the maximum of polysemy, if taken alone, and the minimum of ambiguity in the sense of a contradictory, indefinite emotional configuration (i.e., words like “bomb” or “good”); non-dense words, with the maximum of sense ambiguity and thus with the minimum of polysemy (i.e., words like “to guess” or “anyway”). If dense words, which maintain a strong emotional meaning even when taken in isolation, are identified in a text, they can be grouped according to their co-occurrence in the same text segments, thus creating different symbolic repertoires.

For this purpose, text analysis was performed on the corpus composed of only headlines and subheadings (assumed as text segments) because they concisely provide an immediate image of staking representation with the clearest emphasis. Indeed, newspaper headlines reach an audience considerably wider than those who read the articles. They have certain linguistic features of titles which make them particularly memorable and effective (such as the choice of emotional vocabulary) and encapsulate not only the content but also the orientation and the perspective that the readers should bring to their understanding of the article (Abastado, 1980). They also represent a particularly rich source of information about the field of cultural references. This is because titles “stand alone” without explanation or definition; they depend on the reader recognising instantly the field, allusions, issues, cultural references necessary to identify the content of the articles (Maingueneau, 1996). They thus rely on a stock of cultural knowledge, representations and models of reality that must be assumed to be widespread in the society if the headlines are to have meaning.

Analysis Procedures

Consistently with AET framework, some analysis procedures (cluster analysis and correspondence analysis) were carried out on the text with the help of specific IT programs for text analysis, in our case the software was T-Lab (Lancia, 2004). This manages to obtain groups of words (clusters) which co-occur in the same set of text segments with the highest probability. Then, it allows the detection of the latent dimensions (factors) which define the semantic relationships between these groupings.

In more detail, the T-LAB tool we used for the analysis was the “Thematic analysis of elementary context” which transforms the textual corpus in a digital “presence-absence” matrix. To do that, each headline/subheading was considered as a segment of the corpus (namely, an elementary context unit) and represented a row of the matrix, while all the words present in the corpus represented the columns of the matrix.

The analysis procedure consists of the following steps:

-

a - construction of a data table context units x lexical units (up to 150,000 rows x 3,000 columns), with presence/absence values;

-

b - normalization and scaling of row vectors to unit length (Euclidean norm);

-

c - clustering of the context units (measure: cosine coefficient; method: bisecting K-means);

-

d - filing of the obtained partitions and, for each of them;

-

e - construction of a contingency table lexical units x clusters (n x k);

-

f - chi square test applied to all the intersections of the contingency table;

-

g - correspondence analysis of the contingency table lexical units x clusters.

This procedure therefore performs a type of co-occurrence analysis (steps a-b-c) and, subsequently, a type of comparative analysis (steps e-f-g). In particular, comparative analysis uses the categories of the "new variable" derived from the co-occurrence analysis (categories of the new variable = thematic clusters) to form the contingency table columns.

Each cluster consists of a set of text segments characterised by the same patterns of keywords and can be described through the lexical units (lemmas) and the most characteristic context units (sentences) from which it is composed. Chi-square test (χ2) allows us to test the significance of a word recurrence within each cluster. The function of the co-occurrence of words in the same cluster is hypothesised to reduce the association of meanings attributable to each word (emotional polysemy), thus allowing a thematic domain to be constructed. These clusters of words, that we call Cultural Repertoires, can be considered as the main symbolic areas which refer to the social representation of stalking. The interpretative process of each repertoire (that is labelled by the researcher) is based on using models of affective symbolisation (Carli & Paniccia, 2002) - such as, inclusion/exclusion, power/dependence, trust/mistrust - to give sense to the words co-occurring in each thematic domain1. In this regard, three different areas of affective symbolisations can be proposed which refer to primitive emotions people use to transform reality into something familiar. They deal with symbolic dichotomies which have a clear reference to the body: inside/outside, high/low, in front/behind. The first dichotomy refers to a dynamic of inclusion/exclusion because what is “inside” is represented as something good and friendly, while what is out “outside” is dangerous and rejected. We could continue with the high/low dichotomy which implies symbols of power or with the in front/behind dychotomy which refers to emotional dynamics of true and false. This inferential process also relies on an in-depth qualitative analysis of the text segments derived from the newspaper headlines/subheadings (i.e., the elementary context units) grouped in each cluster.

Then, correspondence analysis enables the exploration of the relationship between clusters in n-dimensional spaces, so as to detect the latent factors which organise the main semantic oppositions in the textual corpus. The relationship between the detected factors and clusters is evaluated through Test Value, a statistical measure with a threshold value (2), corresponding to the statistical significance more commonly used (p = 0.05) and a sign (-/+) which helps in the understanding of the poles of factors detected through Correspondence Analysis.

Results

The analysis detected four Cultural Repertoires (clusters) shaping the social representation of stalking. Table 1 shows both the percentage of the textual corpus of which each cluster is composed of, a list of the most characteristic lemmas (keywords) and some examples of headlines (elementary context units) derived from the newspaper articles analysed.

Table 1

The Most Characteristic Lemmas in Thematic Domains

| Cluster 1 (44.6%): GENDER VIOLENCE |

|---|

| Keywords: woman (χ2 = 31.86) - denounce (χ2 = 9.14) - attack (χ2 = 5.13) - victim (χ2 = 4.32) |

| Increase in cases of stalking: Helping to denounce violence against women |

| Stalking, women are victims twice: “The shame of denouncing limits us” |

| Violence against women: Two attacks a day |

| Cluster 2 (14.9%): PSYCHOLOGICAL VIOLENCE |

| Keywords: sms (χ2 = 48.58) - phone call (χ2 = 29.44) - psychological (χ2 = 23.67) - insult (χ2 = 18.76) - harass (χ2 = 8.39) - annoy (χ2 = 4.59) |

| Stalking, sms, e-mail, harassment: Love-obsession is the new emergency |

| The art of persecution is the new crime: From kidnapping the cat to insulting. As you can destroy a person |

| Violence, assaults, death threats. When love becomes a danger |

| Cluster 3 (12.4%): ANOMIC VIOLENCE |

| Keywords: living together (χ2 = 31.86) - kill (χ2 = 9.14) - home (χ2 = 5.13) - kick (χ2 = 4.32) |

| Ex-Army man threatens and kicks his intolerable next-door neighbour: Arrested for stalking |

| Man kills twice in the same way: He was denounced seven times for stalking |

| Man escapes to kill the woman who accused him of stalking: He shoots her in the face |

| Cluster 4 (28.1%): DOMESTIC VIOLENCE |

| Keywords: wife (χ2 = 19.51) - partner (χ2 = 12.50) - finish (χ2 = 9.53) - trouble (χ2 = 6.95) - beat (χ2 = 5.49) |

| Jealous man persecutes his wife: Arrested for stalking and rape |

| Beatings and threats to ex-wives: Abusive husbands arrested for stalking |

| Violence, hell is in the family: Increase in women’s reports |

Note. The threshold value of Chi-square test (χ2) for each lemma is 3.84 (df = 1; p = 0.05). Textual data were translated into English only for the purposes of the paper.

Cultural Repertoires

Gender Violence (Cluster 1)

This cluster mainly relates stalking to gender violence, given the high rate of stalking cases reported within the female population. “Women” are depicted as “victims” who make an effort to “denounce” stalking, perceived as a social “attack” concerning gender-role differences, as reported in most of newspapers headings. Indeed, the recent cultural changes associated to the increasing independence of women and to the improvement of their socioeconomic status place them at higher risks of victimisation (Martucci & Corsa, 2009). These changes seem to destabilise traditional beliefs and values on the female roles and power relationships between genders in modern society, traditionally characterised by male dominance. In this regard, sexual inequalities, gender role prescriptions and cultural norms and myths about female submissiveness and male dominance, are considered the main socio-cultural factors conducive to stalking (Davis, Frieze, & Maiuro, 2002; White, Kowalski, Lyndon, & Valentine, 2002).

Psychological Violence (Cluster 2)

In this cluster stalking is defined as a form of “psychological” violence characterised by a control dynamic which denies mutual acquaintance and exchange with the other, suggested also by words such as “insult”, “harass”, “annoy”. Indeed, “seeking intimacy can readily merge into a desire to control the victim” (Canter & Ioannou, 2004, p. 123). Newspaper headlines evoke “love-obsession” as the main theme of stalking, within a perverse dynamic characterised by expecting affection from the victim. The indirect communication methods used by the stalker, such as “phone calls”, “sms”, letters, email or fax, represent a way to quickly and easily establish an intimate contact with the victim (Mullen, Pathé, Purcell, & Stuart, 1999). In this sense, stalking assures the illusion of emotional dominance, as well as feeling of immunity and lacking of responsibility (Kamir, 2000).

Anomic Violence (Cluster 3)

In this cluster, stalking is depicted as violation of perceived social boundaries and shared norms of social coexistence, as confirmed by opposite terms such as “living together” or “home” and “kill” or “kick” which seems to deny any form of peaceful exchange. It mirrors an anomic and individualistic culture where violence is a means to create social distance and to impose one’s own superiority by attacking what is seen as dangerous for personal or group identity (Gargiullo & Damiani, 2008). Aggressive-destructive behaviour is recognised as one the main themes which emerges from the examination of the existing literature on stalking (Canter & Ioannou, 2004). Indeed, newspaper headlines mainly report cases in which stalking is associated to murders and other criminal acts. In this sense, stalking is mainly considered as a crime which may easily escalate to physical assault, sexual abuse, and even murder, thus threatening individual safety (Davis, Frieze, & Maiuro, 2002; Meloy, 1997).

Domestic Violence (Cluster 4)

This last cluster relates stalking to domestic violence, in the context of couple relationships, as suggested by the words “wife” and “partner”. It focuses on the marital obligation, characterised by female submissiveness within a patriarchal culture supporting rigid masculine stereotypes about gender and sexual roles (Davis, Frieze, & Maiuro, 2002). In this regard, the co-occurrence between the words “finish”, “trouble” and “beat” seems to suggest this vicious process according to which women’s demand for independence is likely to lead to men’s violent reaction. Indeed, most of newspaper headlines relates stalking to pre-existing dynamics of possession, jealousy and abuse within the family context. Women tend to feel guilty when they fail to fulfil their family duties and thus responsible for their victimisation, contributing to violence perpetration (Voumvakis & Ericson, 1984). As stated by Mullen, Pathé, and Purcell (2009), “When victims do make an assertive attempt to extricate themselves, their partners typically react badly, often in a childlike or pathetic manner that exploits the victims’ guilt and sympathy” (p. 47).

Latent Dimensions

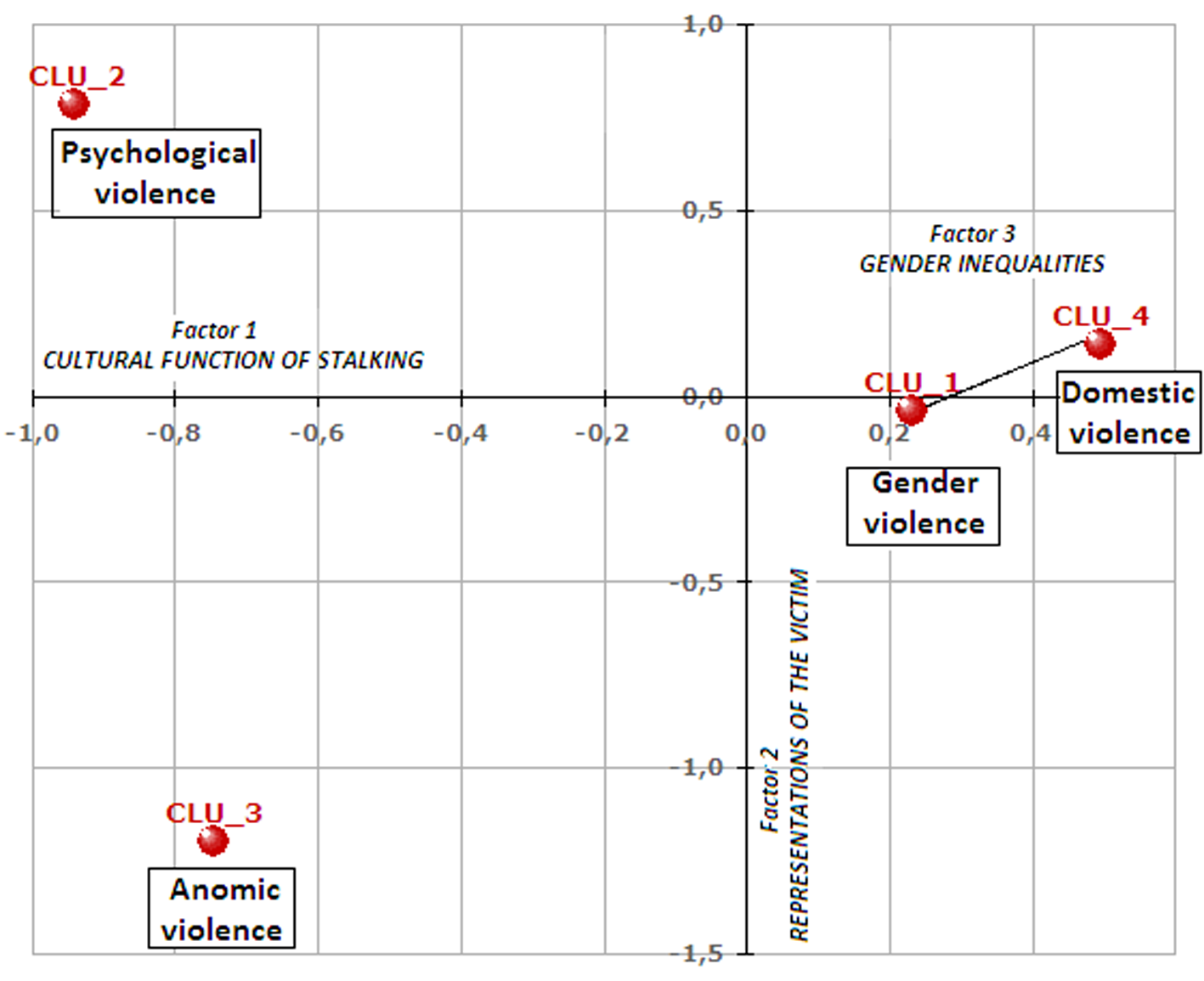

Correspondence Analysis has detected three latent dimensions which organise the main semantic oppositions in the textual corpus, from the different position of clusters in the space, as indicated by Test Value (Table 2). These three latent factors explain all of the data variance (R2 = 100%).

Table 2

Relationship Between Clusters and Factors (Test Value)

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Cultural functions of stalking) | (Representations of the victim) | (Gender inequalities) | |

| Cluster 1 | 4.81 | -0.91 | 8.14 |

| (Gender violence) | |||

| Cluster 2 | -9.21 | 7.66 | -0.52 |

| (Psychological violence) | |||

| Cluster 3 | -6.07 | -9.82 | -1.97 |

| (Anomic violence) | |||

| Cluster 4 | 6.67 | 1.81 | -7.31 |

| (Domestic violence) |

Note. The threshold of test value is (-/+) 2 (p = 0.05). The sign (-/+) indicates the factorial pole to which each cluster is associated.

Below, Figure 1 shows the distribution of clusters within the factorial space, represented graphically on a two-dimensional plane defined by the first (horizontal axis) and the second factor (vertical axis) and, with respect to which, the third factor is ‘‘virtually’’ perpendicular.

Figure 1

Factorial space.

Cultural Functions of Stalking: Infringe Social Norms or Re-Establish Conformist Traditions (Factor 1)

The first factor (40.8% of the total variance) differentiates Clusters 2 and 3 from Clusters 1 and 4 and refers to two main cultural functions of stalking in terms of its different impact on social relationships. On the one hand, stalking has a transgressive function oriented to provocatively infringe social norms regulating social coexistence, such as values of privacy (Cluster 2) and individual safety (Cluster 3). On the other hand, stalking shows a corrective function which aims at re-establishing conformist traditions that were socially accepted in the past, associated to the inferior role of women (Cluster 1) and to the indissolubility of marital institution (Cluster 4).

Representations of the Victim: Object to Possess or Threaten to Attack (Factor 2)

The second factor (37.6% of the total variance) mainly opposes Cluster 2 to Cluster 3 and deals with two different representations of the victim, both related to the difficulty to establish an actual exchange relationship. In Cluster 2 the victim is conceived as something to possess by control mechanism providing illusion of closeness and intimacy. On the contrary, in Cluster 3 the victim is seen as threatening personal power and self-preservation, and thus is attacked within a violent dynamics characterised by progressive distancing and emotional refusal.

Gender Inequalities: Family or Social Role of Women (Factor 3)

The third factor (21.6% of the total variance) differentiates Cluster 1 from Cluster 4 and refers to a double-faceted dimension of violence against women with regard to gender inequalities. On the one hand, Cluster 4 focuses on the traditional image of women within the family context as wives subjects to marital obligation and domestic violence. On the other hand, Cluster 1 looks at gender violence as denial of the role and rights of women in the wider social context, historically characterised by male dominance.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to provide a cultural portrait regarding the main social representations of stalking from an analysis of the Italian press. Four main cultural repertoires were detected which respectively refer to gender (Cluster 1), psychological (Cluster 2), anomic (Cluster 3) and domestic (Cluster 4) violence, conceived as existing along three latent dimensions.

The first dimension shows two different cultural areas which portray stalking as a phenomenon whose origin is both ancient and modern (Centro documentazione donna di Modena, 2010). From a historical perspective, stalking seems to refer to the “gap” between traditional values on the wane - such as the institution of marriage and the traditional role of women (Cluster 4) - and most recent values - such as the independence of women in modern society (Cluster 1). In this sense, the difficulty of criminology to define this phenomenon mainly depends on the paradoxical nature of stalking as both conformist and illegal behaviour (Maugeri, 2010). Indeed, on the one hand, stalking represents an improper amplification of certain social behaviours that were permitted in the past, such as the exasperation of the courtship ritual (Martucci & Corsa, 2009). On the other hand, it can be considered as a form of “asocial and destructive behaviour” (Gargiullo & Damiani, 2008), disruptive of shared values - such as privacy (Cluster 2) and individual safety (Cluster 3) - and derived from some changes occurred in contemporary society such as the tendency to voyeurism, hero worship, the lack of boundaries between the public and private sphere, and the development of new mediated communication.

The second dimension suggests two different forms of stalking based on a double-faceted representation of the victim as “extraneousness” on which to exert power. By extraneousness we mean the diversity of the “others”. Collusive processes, regarded as shared affective symbolisations, should thus serve as a means to represent the reality, give sense to social relationships and to reduce the unknown or the different to something known. Indeed, in order to promote social coexistence it is necessary that a social system is “open to dialog with the extraneous, in reciprocal processes of assimilation and accommodation which allow for the bridging of differences and interaction aimed at a productive objective” (Carli & Giovagnoli, 2011, p. 142). According to our results, on the one hand, the extraneous is “converted” by a process of transformation and assimilation into the dominant culture (Cluster 2). On the other hand, the extraneous is “attacked” and rejected because it is perceived as a danger to one’s own stable and repetitive identity (Cluster 3). In this sense, this result seems to be consistent with wider literature according to which stalking can be classified as minor or mild and as severe or violent (Löbmann, 2002; Velten, 2003). The first refers to constant attempts of communication against the victims’ will, i.e. by sending them unwanted items; violent stalking, on the contrary, means that the perpetrators insult and abuse the victims, threaten them, damage their property or physically attack the victims. The power relationship between stalker and victim is thus grounded on a double-faceted dynamics characterised by both control and destruction. If we consider such processes as simultaneously present, then we understand the high risk of violence escalation in stalking behaviour (Baldry & Roia, 2011), which can result in murder as an extreme act to establish control over the victim’s life. Because control and destruction are put on the same latent factor, they can be conceived as different modes of expressing the same underlying processes - along a continuum - rather than as opposite themes. As revealed by a previous study (Canter & Ioannou, 2004), possession and aggression are regarded as one area of the stalker wishing to reduce the victim to something less than fully human that would be under his/her control. In addition, according to our study results, both these dynamics of stalking share a common destructive function oriented to disrupt social relationships, as indicated by the first latent factor. In this sense, control and destruction could reflect a different intensity of the stalker’s attempts for contact with the victim, possible due to different stages in the development of the stalking process. When the stalker fails to maintain a psychological control over the victim, the stalker’s attempts may thus culminate in a violent attack on the victim.

Then, the third dimension reveals the strong link between stalking and violence against women, as already indicated by previous research which related stalking to both gender-based (Cluster 1) and domestic violence (Cluster 4) (Weiß & Winterer, 2008). In this regard, the persistence of a patriarchal culture in the social hierarchy seems to have favoured the legitimisation of violence against women as functional to the maintenance of an unequal distribution of roles (Basaglia, Lotti, Misiti, & Tola, 2006). Indeed, the analysis of the press discourse on stalking seems to offer a stereotypical portrait of women, mainly depicted as social victims or weak wives/partners, subjected to male dominance. When males are suspects and women are victims, the story takes on greater newsworthiness (Pritchard & Hughes, 1997), perhaps because it resonates with larger cultural narratives. Such news not only conforms to cultural myths, but assists in enforcing them as well, because cultural narratives of crime serve the function of providing warnings and suggestions for personal risk management and sense making (Spitzberg & Cadiz, 2002). Besides, as stated by Corradi (2008), violence against women requires a complex analysis that takes into account some changes that have negatively affected the male identity. These changes do not depend only on the development of women’s social conditions but are also due to wider issues related to the Italian context, such as the globalisation of labour market, the lowered prestige of certain professions and the loss of status of middle classes. The financial crisis has led women to enter into the workforce in order to contribute to family income, within a global and competitive economy. This situation has affected the traditional gender roles, according to which males are mainly responsible for the economic support and protection of the family, while females are expected to restrict themselves to child-rearing and domestic activities. Nowadays, women are provided with equal opportunities in education and employment; instead the male role has increasingly become marginal within the family. In this regard, economic resources are demonstrated to be powerful determinants of whether women enter, remain in, or leave abusive partners (Anderson & Saunders, 2003; Lambert & Firestone, 2000), because they can affect, in turn, the access to external services or assistance and contribute to overcome women’s isolation and economic dependence on partners. Stalking, as well as other control strategies (i.e., intimidation, degradation, isolation, etc.), could thus represent an extreme attempt to maintain or restore male authority and to secure gender-based privilege by depriving women of their rights and liberties (Corradi, 2008).

Conclusions

A careful consideration of these cultural areas could, therefore, provide a key to a social and historical contextualisation of stalking in Italy, in order to re-think work practices within institutional agencies that deal with this problem. For instance, the study results show that gender violence could represent a useful framework to analyse stalking in the Italian context. In this sense, employers, housing providers, educators and other responsible parties can prevent many cases of stalking by having a clear and comprehensive policy oriented to equal opportunities and respect for human rights related to gender issues. Primary prevention could thus be promoted, at both school and workplace, across three levels according to an ecological model:

-

Individual/relationship level, such as individuals’ beliefs in rigid/unequal gender roles, and attitudinal support for violence against women;

-

Community/organisational level, such as culturally specific gender norms, and male peer and/or organisational cultures that are violence-supportive or provide weak sanctions against violence and/or gender inequality;

-

Societal level, such as institutional practices and widespread cultural norms providing support for, or weak sanctions against, violence against women and/or gender inequality.

In addition, research shows that the stalker’s desire to control the victim by searching intimacy with him/her could easily lead to violence and physical aggression, because both these behaviours share a common destructive psychological root. The victim, regarded as object to possess, may thus become an object to attack when control strategies fail. Therefore, local law enforcement agencies should not minimise repeated unwanted communications (such as phone calls, letters, email, sms), because they could represent potential signals of stalking escalation, if they are reported over time.

Then, a relevant component of stalking which emerges from this study is its paradoxical nature, as both illegal and conformist behaviour, aimed at both infringing social norms and re-establishing socially accepted traditions. This means that any institutional agency has to take into account that people who experience stalking may accept their victimisation as something normal, thus contributing to violence perpetration, as it happens in domestic violence. Therefore, it is important to support victims to take responsibility for his or her safety by becoming familiar with local stalking laws, resources, and law enforcement policies and also to emphasize that a victim must be assertive to ensure that safety measures are in place, as in the case of protective orders.

The implementation of effective prevention and intervention efforts in the field of stalking thus requires integrating criminological and psychiatric issues into a psychosocial perspective, which allows the detection of social and cultural dynamics triggering this phenomenon.

However, some limitations need to be acknowledged regarding the present study, because of its merely qualitative and exploratory nature. Therefore, it does not consent to assess the real spread of stalking and the different related behaviours in the Italian context, rather it only provides some cultural cues and thematic areas that need further investigation.

In addition, it is not possible to detect a direct relationship between our research findings and social representations in the Italian population. Indeed, the cultural models of stalking could be characterised by higher variability compared to what emerges from the analysis of the popular press. In this regard, future research could carry out a representative nationwide survey in order to confirm and better explain our results. This would also consent to perform secondary sub-group analyses by geographic location and socio-demographic characteristics - such as gender, age, education, employment, etc. - to further disentangle the cultural models of stalking in the general population. Another limitation deals with the specific focus on newspapers’ analysis that could limit the source of mass media contributing to stalking discourse in the Italian context. A future research recommendation would thus be to include other forms of mass communication (i.e., radio, television, internet, etc.) which could differently influence the social representation of the topic.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (