While dimensions of romantic relationships such as relationship satisfaction, empathy towards the partner, and dyadic coping strategies remained predominately uninvestigated until the early nineties, in recent years, the study of such constructs has become an emerging topic attracting a growing number of theoretical and research contributions (Bodenmann, 2000; Bodenmann, Pihet, & Kayser, 2006; Story & Bradbury, 2004). Although prior investigations have been conducted which ascertain the impacts of both dyadic coping and dyadic empathy on relationship satisfaction, such streams of research have traditionally been conducted in parallel to one another (Bodenmann & Randall, 2012; Péloquin & Lafontaine, 2010). Thus, there is a continuing need for research aimed at investigating links between these variables both through direct associations and through interactions between factors brought to the dyad from each member of the couple (Davila, Karney, Hall, & Bradbury, 2003). To date, no inquiry has been conducted on how dyadic coping and dyadic empathy may interact to shape the quality of couple relationships. In an effort to address this lack of literature, the current research aims to investigate both the individual-level and dyadic associations between dyadic empathy, dyadic coping, and relationship satisfaction. Moreover, we sought to explore and further understand the mechanisms by which dyadic empathy relates to relationship satisfaction between partners by examining the mediating role that dyadic coping might play in the relationship linking empathy and satisfaction.

Link Between Dyadic Empathy and Relationship Satisfaction

While historical definitions of the concept of empathy were divided between two theoretical conceptualizations, there now exists a general consensus that empathy is actually a two-dimensional concept that encompasses aspects of both early definitions (for a review see Péloquin & Lafontaine, 2010). Some early theorists defined empathy as an emotionally-based concept (Batson, Fultz, & Schoenrade, 1987; Bryant, 1987; Eisenberg & Strayer, 1987), while others postulated that empathy is rooted in cognitive processes (Hogan, 1969; Wispé, 1986). Such opposing theories were eventually unified, as the contemporary understanding of this concept postulates that empathy embodies both emotional and cognitive facets (Davis, 1994; Duan & Hill, 1996; Hoffman, 1984; Strayer, 1987). The cognitive, or perspective-taking dimension of empathy involves the ability to understand the point of view of another person (Hogan, 1969), while the emotional, or empathic concern dimension corresponds to the emotional reactions felt in response to another person’s emotional experience (Davis, 1983). Drawing from both cognitive and emotional components, empathy can be considered as one’s ability to understand and share in the emotions of others (Cohen & Strayer, 1996). Such a definition encompasses a general conceptualization of empathy as applying to empathic tendencies experienced in general social interactions with others, and must be distinguished from dyadic empathy, which refers exclusively to empathy expressed toward a romantic partner (Long, 1990).

From a theoretical standpoint, attachment theory serves as the cornerstone to understanding the link between dyadic empathy and relationship satisfaction. According to Bowlby, one must first experience sufficient attachment security in order for their own caregiving system to be activated and responsive to the signals of distress exerted by their partner (Bowlby, 1969; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005). The caregiving system serves to alleviate distress and promote a sense of felt security in close relationships, and is particularly important in the context of couple relationships, as partners rely on one another for comfort, support, and protection in times of stress (Bowlby, 1969). Empathy is considered an essential component of the caregiving system, and serves as an important mechanism whereby signals of a partner’s distress can be recognized, and in turn, responded to (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005). Along with the rest of the caregiving system, one’s ability to express empathy is facilitated by feelings of attachment security, and can also be hindered or suppressed by attachment insecurity (Feeney & Collins, 2001). In a similar vein, suppressed caregiving abilities stemming from attachment insecurity may translate into a lack of empathy for one’s romantic partner. This lack of empathy may serve to keep a partner at a distance, and may inhibit intimacy and closeness. As such, effective romantic caregiving as demonstrated by a partner’s ability to experience and express empathy is closely tied to relationship quality and satisfaction, and is essential to fostering closeness and support during times of distress (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

An impressive body of literature attests to the impacts of both the emotional and cognitive facets of empathy on couple relationship satisfaction. Previous studies indicate that general and dyadic forms of empathy play a role in predicting relationship quality and functioning (e.g., Boettcher, 1978; Busby & Gardner, 2008; Davis & Oathout, 1987; Franzoi, Davis, & Young, 1985; Larned, 2006; Long, Angera, Carter, Nakamoto, & Kalso, 1999). Specifically, Davis and Oathout (1987) and Franzoi and colleagues (1985) demonstrated that cognitive, or perspective-taking empathy is a significant predictor of couple satisfaction for both college-age males and females. Their results also revealed that while empathy predicted an individual’s own relationship satisfaction among both males and females, the empathic tendencies of female partners may also lead to increased relationship satisfaction among their male partners (Davis & Oathout, 1987; Franzoi et al., 1985). Moreover, previous research has determined that both cognitive and emotional facets of dyadic empathy contribute to relationship satisfaction by diffusing the negative impact of stressful life events on couple relationships (Boettcher, 1978; Busby & Gardner, 2008; Davis & Oathout, 1987; Long et al., 1999). In a similar vein, research conducted by Larned (2006) demonstrated that both perceived expressed and received dyadic empathy are significant predictors of relationship satisfaction among both males and females in married, heterosexual couples. Collectively speaking, the aforementioned studies provide convincing evidence for the important role held by both cognitive and emotional dimensions of empathy in fostering and sustaining romantic relationship satisfaction.

The Effect of Dyadic Coping on Relationship Satisfaction

The study of dyadic coping has recently attracted a growing number of empirical contributions, as researchers have begun to acknowledge the importance of examining coping not strictly as a general construct pertaining to personal well-being, but within the context of romantic relationships (e.g., Bodenmann, Kayser, & Revenson, 2005). Whereas a more general conceptualization of coping pertains to the strategies employed to manage stressful life circumstances, dyadic coping involves both members of a couple and refers to the interplay between the stress signals of one partner and the coping reactions of the other (Bodenmann et al., 2005). By strict definition, dyadic coping is conceptualized as a stress communication process which initiates both partners’ coping responses (Bodenmann, 2005).

This dyadic phenomenon is activated when one partner’s appraisal of stress is communicated to his or her partner. This partner then perceives and interprets the stress signal emitted and responds with either positive or negative coping strategies in an attempt to assuage his or her partner’s feelings of stress (Bodenmann, 2005). Bodenmann’s (2005) work describes a number of different dyadic coping strategies used within romantic relationships. Negative dyadic coping refers to displaying overt disinterest or sarcasm toward the partner’s stress, employing coping strategies which are not authentic, and responding to the stress signal emitted in a reluctant manner, or not believing that the partner actually needs support. Supportive dyadic coping involves one partner helping the other to manage the stressful event. Delegated dyadic coping refers to one partner adopting additional tasks in order to relieve the burden of the other. Finally, common dyadic coping refers to both partners jointly working to resolve the stressful situation together (Bodenmann, 2005; Bodenmann & Cina, 2006).

Dyadic coping serves two primary functions: the reduction of stress for both partners, and the enhancement of relationship quality. In situations where one partner is faced with a significant stressor or both members of the couple are challenged by a shared stressor, enacting dyadic coping strategies should help to manage distress. In addition to its stress-reduction purpose, dyadic coping is considered to foster a sense of we-ness among couples (Bodenmann, 2005). Dyadic coping is considered essential to relationship quality and well-being, as positive dyadic coping fosters mutual trust, respect, relationship commitment, and a sense that the relationship is comforting and supportive (Bodenmann, 2000).

Numerous recent studies attest to the impact of dyadic coping on couple relationship satisfaction (e.g., Bodenmann, 2005; Bodenmann et al., 2006; Bodenmann, Charvoz, Cina, & Widmer, 2001; Bodenmann & Cina, 2006; Papp & Witt, 2010; Wunderer & Schneewind, 2008). Findings from a meta-analysis conducted by Bodenmann (2000) provide convincing evidence for the positive relationship between dyadic coping and satisfaction among both community-based and clinical populations. Of the numerous studies examined, Bodenmann found greater positive dyadic coping among couples higher in relationship satisfaction compared with distressed couples, who reported more frequent use of negative dyadic coping strategies. Moreover, the association between dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction is considered long-standing, as evidenced by results from a longitudinal study indicating that couples high in marital satisfaction displayed more positive supportive dyadic coping and common dyadic coping than did couples who were separated or divorced by the 5-year follow-up (Bodenmann & Cina, 2006). Findings from clinical intervention studies also provide further support for the key role held by dyadic coping in determining relationship satisfaction, as distressed couples participating in a treatment program aimed at enhancing dyadic coping strategies experienced significant increases in marital quality, and appraised their relationships as substantially improved even after one year (Bodenmann et al., 2001). In addition to literature supporting a link between an individual’s own dyadic coping and their own relationship satisfaction among both males and females, research also suggests that for females, both their own and their partner’s dyadic coping influence their level of relationship satisfaction (Bodenmann et al., 2006; Papp & Witt, 2010).

The literature reviewed above both highlights the key associations between: a) dyadic empathy and relationship satisfaction, and b) dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction, in addition to emphasizing certain gaps in existing literature. Given that empathy can be thought of as a trait, and dyadic coping is conceptualized as behavioral strategies employed to reduce stress, dyadic coping is more likely to be influenced by dyadic empathy than the opposite, and therefore, coping may act like a mediator in the relationship between dyadic empathy and relationship satisfaction. However, despite the positive contributions of such constructs to romantic relationship satisfaction, in addition to theories suggesting that such variables are closely linked (e.g., Bodenmann, 2005; O’Brien, DeLongis, Pomaki, Puterman, & Zwicker, 2009), and research confirming the profound roles held by dyadic empathy and dyadic coping in developing and maintaining romantic relationship satisfaction, no study has examined such a mediational model. In line with these considerations, the present study seeks to address such gaps in existing literature by investigating the associations between dyadic empathy, dyadic coping, and relationship satisfaction, in addition to exploring the possible mediational influence of dyadic coping on the link between dyadic empathy and relationship satisfaction.

Objectives and Hypotheses of the Present Study

The primary objectives were to investigate: a) possible associations between dyadic empathy, dyadic coping, and relationship satisfaction within a mediational model; and b) to examine both actor and partner effects on each of the aforementioned variables (e.g., examining whether each partner’s dyadic empathy is related to his or her own perceptions of relationship satisfaction, and to the relationship satisfaction of the partner).

Drawing from existing research and theoretical contributions, it was hypothesized that: a) one’s own cognitive (perspective-taking) and emotional (emotional concern) dimensions of dyadic empathy would positively predict both one’s own and the partner’s dyadic coping processes and relationship satisfaction; b) one’s own dyadic coping would be positively related to one’s own relationship satisfaction, and to that of the partner; and c) both one’s own and the partner’s dyadic coping processes would mediate the association between one’s own dyadic empathy and relationship satisfaction.

Method

Participants

Heterosexual Canadian couples were invited to participate in this study. In order to participate, individuals had to satisfy the following eligibility criteria to ensure relational commitment between partners: a) be 18 years of age or older; b) have been involved in a heterosexual romantic relationship with their current partner for at least 12 months; and c) have cohabited with their partner for a minimum of six months. A sample of 187 couples was recruited for participation. The mean age of female participants was 30.25 years (SD = 9.55, range = 19.33 to 77.58), and the mean age of male participants was 32.52 years (SD = 10.69, range = 20.42 to 78.83). The average duration of current romantic relationships was 6.68 years (SD = 8.30) and the average duration of cohabitation was 4.78 years (SD = 7.82). Of the couples, 30% were married and 14% had children with their current partner. The average annual income per individual was $45,157.60 ($49,070.12 for men and $40,991.93 for women). Participants were primarily Caucasian (78%) and were all English-speaking.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through various media outlets (i.e., advertisements in local newspapers, poster advertisements, and recruitment booths at pertinent events). Participants registering for participation were informed that the purpose of the study was to examine couple relationship functioning. Prior to scheduled appointments, participants were informed of the voluntary nature of the study, the particular experimental procedures involved, as well as their right to withdraw from the study at any given time, consequence-free. To ensure anonymity, participants were assigned identification numbers to appear on all documentation in lieu of revealing information (i.e., participants’ names). Testing appointments required the attendance of both partners, and opened with the completion of an informed consent document followed by completion of a questionnaire package. Participants were then provided with forty-dollars per couple as compensation. The present study has been approved by the university research ethics committee.

Measures

Demographic Information

Participants were asked to provide both personal information (e.g., age, gender, and annual revenue) and relationship information (e.g., length of relationship, length of cohabitation, marital status, and number of children).

Dyadic Empathy

The Interpersonal Reactivity Index for Couples (IRIC; Péloquin & Lafontaine, 2010) is a 13-item self-report questionnaire that measures cognitive and emotional aspects of dyadic empathy. Cognitive aspects of dyadic empathy are measured by the Dyadic Perspective-Taking scale, which evaluates individuals’ ability to consider their partners’ perspective. A sample item from this scale reads: “I try to look at my partner’s side of a disagreement before I make a decision”. Emotional aspects are measured by the Dyadic Empathic Concern scale, which evaluates individuals’ feelings of sympathy and concern for their partners. A sample item from this scale reads: “I often have tender, concerned feelings for my partner when he/she is less fortunate than me”. Each questionnaire item is measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale, with responses ranging from: (0) “Does not describe me well” to (4) “Describes me very well”. Respective items are summed to obtain scales scores (scores range from 0 to 24 for the Dyadic Perspective-Taking scale, and from 0 to 28 for the Dyadic Empathic Concern scale). Elevated scores represent greater dyadic perspective-taking and dyadic empathic concern. In a study examining various samples of couples, the IRIC demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency and adequate convergent, concurrent, and predictive validity (Péloquin & Lafontaine, 2010). Moreover, reliability coefficients calculated in the present study revealed alphas of .82 (.79 for men and .84 for women) for the Dyadic Perspective-Taking scale and .69 (.69 for women and .69 for men) for the Dyadic Empathic Concern scale.

Dyadic Coping

The Dyadic Coping Inventory (DCI; Bodenmann, 2008) is a 37-item self-report questionnaire that measures the degree to which couples support and actively help one another during times of stress. Each questionnaire item is measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale, with responses ranging from: (1) “Very rarely” to (5) “Very often,” used to rate individuals’ own coping processes (i.e., stress communication, supportive dyadic coping, delegated dyadic coping, and negative dyadic coping), their perceptions of their partner’s coping processes (i.e., stress communication, supportive dyadic coping, delegated dyadic coping, and negative dyadic coping), and their perceptions of their coping processes as a couple (i.e., common dyadic coping). While this measure consists of several subscales, only the Dyadic Coping by Oneself was used in the present study, as it allows participants to self-evaluate their own dyadic coping processes. A sample item from this scale reads: “I take on things that my partner would normally do in order to help him/her out.” Respective items are summed to obtain scale scores, ranging from 15 to 75. Elevated scores represent increased experiences of positive dyadic coping. In an evaluation of its internal structure with a sample comprised of 709 English-speaking students involved in a couple, the DCI has demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency and concurrent validity (Levesque, Lafontaine, Caron, & Fitzpatrick, in press). Moreover, reliability coefficients calculated in the present study on the Dyadic Coping by Oneself scale revealed an alpha of .81 (.77 for men and .84 for women).

Relationship Satisfaction

The Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS-4; Sabourin, Valois, & Lussier, 2005) is a widely-used self-report measure of dyadic functioning used to evaluate the degree of couple relationship satisfaction experienced by individuals in romantic relationships. The DAS-4 is a brief four-item measure derived from the original 32-item DAS (Spanier, 1976). A sample item from this questionnaire reads: “The descriptions on the following line represent different degrees of happiness in your relationship. The middle point, “happy” represents the degree of happiness of most relationships. Please circle the number, which best describes the degree of happiness, all things considered, of your relationship.” The first three items in the questionnaire employ a six-point Likert-type response format, with responses ranging from (0), “All the time,” to (5) “Never”. These three items evaluate individuals’ perceptions regarding the quality of life shared with their partners. The fourth item measures individuals’ subjective experiences of happiness in their couple relationships, and employs a seven-point Likert-type response format, with responses ranging from (0) “Extremely unhappy,” to (6) “Perfectly happy”. A total score is calculated by summing all items (scores range from 0 to 21). Elevated scores represent increased relationship satisfaction. The four-item scale has been found to be as effective in predicting couple dissolution as the 32-item version, and demonstrates good internal consistency (Sabourin et al., 2005). Moreover, reliability coefficients calculated in the present study for the DAS-4 revealed an alpha of .77 (.83 for men and .71 for women).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

A total of 193 couples participated in this ongoing study. In order to optimize the sample size, missing values were estimated using Expectation Maximization. None of the items had more than 5% missing values, indicating that this option was appropriate for use (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Six couples were detected as multivariate outliers and subsequently removed from the analyses, leaving a total of 187 couples.

The means and standard deviations for the main variables (dyadic empathic concern, dyadic perspective-taking, dyadic coping, and relationship satisfaction) are presented in Table 1, along with the results of an analysis of variance exploring gender differences between male and female participants. Results revealed a significant gender difference for dyadic coping, as women generally reported experiencing more positive dyadic coping than men.

Table 1

Means and Standard Deviations for Dyadic Empathy, Dyadic Coping, and Relationship Satisfaction

| Variables | Men (n = 187)

|

Women (n = 187)

|

F(1, 372) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Empathic Concern | 23.22 | 3.45 | 23.69 | 3.46 | 1.74 |

| Perspective-Taking | 16.23 | 4.06 | 16.03 | 4.21 | 0.23 |

| Dyadic Coping | 59.89 | 6.35 | 61.92 | 6.97 | 8.61** |

| Relationship Satisfaction | 17.21 | 2.92 | 17.19 | 2.80 | 0.01 |

**p < .01.

Correlations among main variables for men and women are presented in Table 2. One’s own dyadic empathic concern was related to one’s own dyadic perspective-taking for both men and women participants, but not to that of their partners’. Moreover, results indicated that both forms of one’s own dyadic empathy were related to greater one’s own dyadic coping and greater one’s own relationship satisfaction for men and women. While women’s dyadic empathic concern was related to their partners’ dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction, men’s dyadic empathic concern was only linked to their partners’ relationship satisfaction. Women’s dyadic perspective-taking was correlated with their partners’ relationship satisfaction, while men’s dyadic perspective-taking was correlated with their partners’ dyadic coping. Results indicate that dyadic coping was associated with increased relationship satisfaction, both for oneself and between partners. Results also revealed an association between men and women’s dyadic coping. Finally, one’s own relationship satisfaction was positively correlated with that of their partners. No correlation was found between partners’ dyadic empathic concern nor between partners’ dyadic perspective-taking.

Table 2

Correlations Between Dyadic Empathy, Dyadic Coping, and Relationship Satisfaction Among Men and Women

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. EC M | - | |||||||

| 2. EC W | .12 | - | ||||||

| 3. PT M | .44*** | .05 | - | |||||

| 4. PT W | .04 | .36*** | .06 | - | ||||

| 5. DC M | .43*** | .22** | .43*** | .12 | - | |||

| 6. DC W | .09 | .58*** | .15* | .54*** | .31*** | - | ||

| 7. DAS M | .44*** | .18* | .29*** | .17* | .51*** | .26*** | - | |

| 8. DAS W | .17* | .47*** | .12 | .32*** | .33*** | .55*** | .40*** | - |

Note. EC = Dyadic Empathic Concern; PT = Dyadic Perspective-Taking; DAS = Relationship Satisfaction; DC = Dyadic Coping; M = Men; W = Women.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Structural Equation Modeling

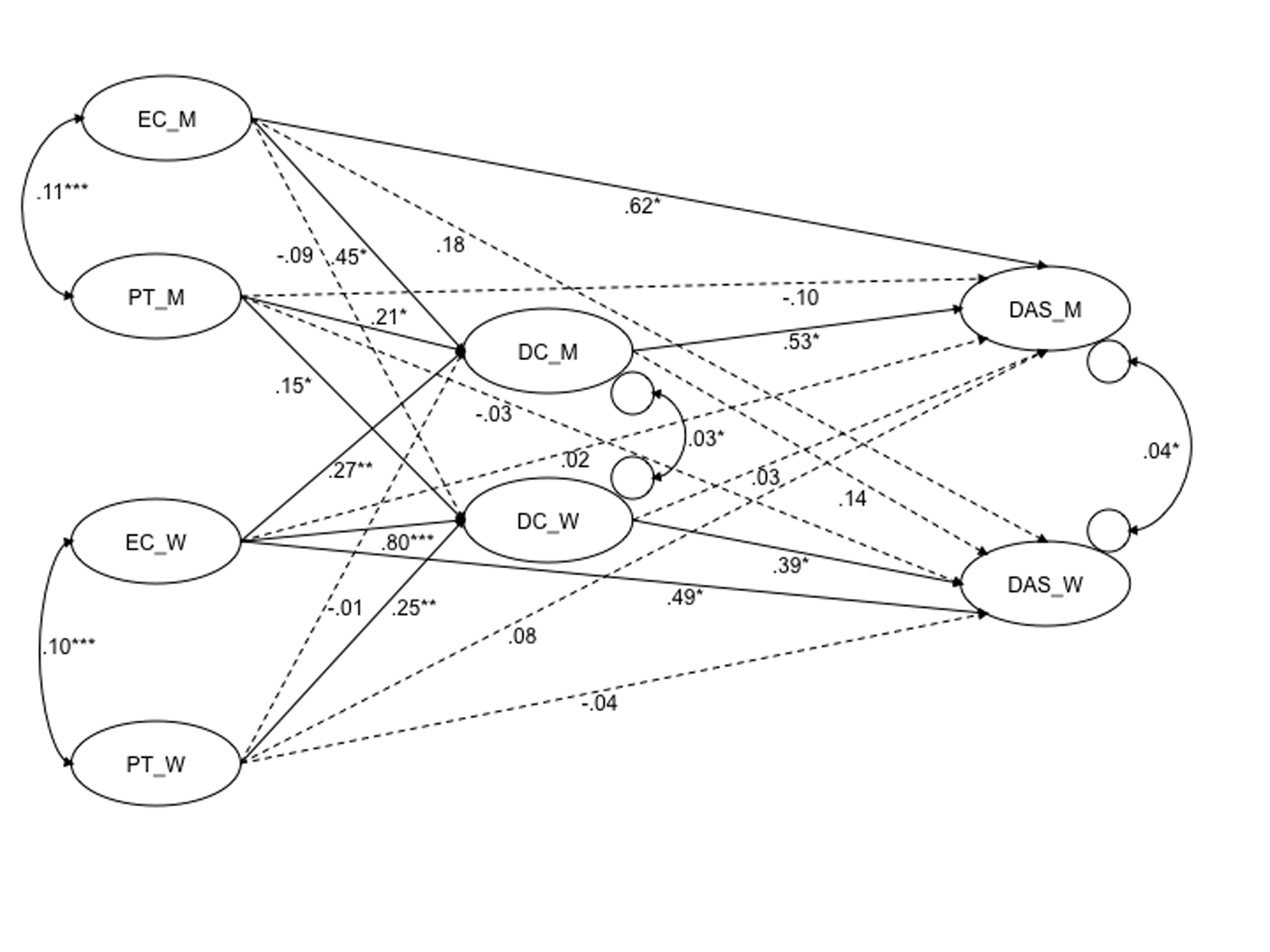

An Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006) using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to establish the mediating role of dyadic coping in the associations between dyadic empathy (cognitive and emotional dimensions) and relationship satisfaction. Both intrapersonal (actor effect) and dyadic (partner effect) relationships between these variables were explored. The structural equation model (see Figure 1) was conducted using the maximum-likelihood method available in Amos (Arbuckle, 2011). Bias corrected (BC) confidence interval was used with bootstrapping (5000 samples) method in order to obtain more powerful confidence interval (CI) limits for indirect effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). The fit of the final model was deemed satisfactory (χ2(271) = 381.90, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .94).

Figure 1

Unstandardized Coefficients for the Structural Equation Model showing the mediating role of dyadic coping in the Associations between dyadic empathy and relationship satisfaction for both partners.

Note. EC = Dyadic Empathic Concern; PT = Dyadic Perspective-Taking; DAS = Relationship Satisfaction; DC = Dyadic Coping; M = Men; W = Women.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

In order to create stable indicators, items from the dyadic empathy scale and items from the dyadic coping scale were divided randomly to one of three parcels and subsequently averaged (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). As the relationship satisfaction questionnaire consisted of only four items, four indicators were used. To guarantee that concepts were assessed equivalently between men and women, and to assure the nonindependency of data in the model, all factor loadings of the indicators where constrained to be equivalent for women and men (Kenny et al., 2006). Furthermore, because the indicators for each latent variable were the same for both men’s and women’s portion of the model, correlation was permitted between the variance (error term) for men and women. For example, men’s first indicator of the empathic concern dimension of dyadic empathy was correlated with women’s first indicator of dyadic empathic concern. Based on the results of the correlational analyses, men’s latent variables of dyadic empathy (empathic concern and perspective-taking) were permitted to correlate in the final model, as well as women’s latent variables of dyadic empathy (empathic concern and perspective-taking). However, there was no correlational path between individuals’ dyadic empathy and their partners’ dyadic empathy, as no significant correlations were found in the preliminary analyses. Moreover, the residuals of the endogenous latent variables of dyadic coping reported by men and women were allowed to correlate in the final model because preliminary results demonstrated significant correlations. The same procedure was used for relationship satisfaction.

Factorial invariance across gender was demonstrated by a non-significant chi-square difference (Δχ2(9) = 12.19, p > .05) between a constrained measurement model (i.e., all factor loadings of the indicators where constrained to be equivalent for women and men) and an unconstrained model (i.e., freely estimated measurement model), indicating that concepts were assessed equivalently between men and women.

Actor Effects

In the men’s portion of the model (the upper half of Figure 1), dyadic empathy latent variables (empathic concern and perspective-taking) predicted greater dyadic coping. Moreover, dyadic coping predicted greater relationship satisfaction. The direct link between men’s dyadic empathic concern (but not dyadic perspective-taking) and their relationship satisfaction was also positively significant. These findings were also duplicated for the women’s portion of the model (the lower half of Figure 1), indicating similarity between men and women.

Partner Effects

When examining the dyadic aspects of the model, different results were obtained between men and women. Men’s dyadic perspective-taking (but not dyadic empathic concern) was positively linked to their partner’s dyadic coping. Alternately, women’s dyadic empathic concern (but not dyadic perspective-taking) was positively linked to their partners’ dyadic coping. No significant links were found between one’s own dyadic coping and their partner’s relationship satisfaction and between one’s own dyadic empathy and their partner’s relationship satisfaction.

Indirect Effects

Using bias-corrected bootstrapping estimates, all possible indirect effects were evaluated (see Table 3) and were decomposed into an actor’s effect (indirect effect running through one’s own dyadic coping) and a partner’s effect (indirect effect running through the partner’s dyadic coping).

Table 3

Dyadic Indirect Effects of Dyadic Empathy on Relationship Satisfaction

| Predictor | Outcome | Actor Effect

|

Partner Effect

|

Total Indirect Effect

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | B | B | SE | p | ||

| EC_M | DAS_M | .242 | -.003 | .240 | .157 | .044 |

| EC_M | DAS_W | .063 | -.036 | .027 | .155 | .852 |

| PT_M | DAS_M | .110 | .004 | .114 | .085 | .059 |

| PT_M | DAS_W | .029 | .057 | .085 | .071 | .079 |

| EC_W | DAS_M | .025 | .144 | .168 | .332 | .450 |

| EC_W | DAS_W | .313 | .037 | .350 | .260 | .109 |

| PT_W | DAS_M | .008 | -.004 | .004 | .085 | .942 |

| PT_W | DAS_W | .096 | -.001 | .095 | .086 | .143 |

Note. EC = Dyadic Empathic Concern; PT = Dyadic Perspective-Taking; DAS = Relationship Satisfaction; M = Men; W = Women.

Results provided evidence for partial mediation of dyadic coping on the association between dyadic empathic concern and relationships satisfaction at the men’s individual (actor) level only. No other significant mediation was found, although the indirect effect of dyadic coping on the association between dyadic perspective-taking and relationship satisfaction at the men’s individual level was marginally significant.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate a theoretical model specifying the direct and indirect associations between dyadic empathy, dyadic coping, and relationship satisfaction in a sample of community-based couples, as well as to examine both actor and partner effects on each of these variables. We expected that dyadic empathy would be associated with both dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction, and that dyadic coping would also be associated with relationship satisfaction. Moreover, we expected that both one’s own and the partner’s dyadic coping processes would mediate the association between one’s own dyadic empathy and relationship satisfaction.

Actor Effects

The present study’s hypothesis on the link between one’s own dyadic empathy and one’s own dyadic coping was confirmed. In men and women, one’s use of perspective-taking and emotional concern significantly improved one’s dyadic coping processes. As previously mentioned, dyadic empathy and dyadic coping play profound roles in developing and maintaining romantic relationship satisfaction (e.g., Bodenmann, 2000; Boettcher, 1978; Busby & Gardner, 2008; Davis & Oathout, 1987; Long et al., 1999), and yet this is the first study to date to have examined the link between dyadic empathy and dyadic coping. In support of this association, this finding suggests that the ability to understand the point of view of and to share in the emotional experience of one’s romantic partner are related to the ability to communicate stress to one’s romantic partner. In other words, dyadic empathy is conducive to the resolution of stressful situations.

The present study’s hypothesis on the link between one’s own dyadic empathy (cognitive and emotional) and one’s own relationship satisfaction was partially confirmed. The use of empathic concern significantly improved one’s relationship satisfaction. However, despite the importance accorded to perspective-taking in marital adjustment and dyadic well-being (Long et al., 1999; Rowan, Compton, & Rust, 1995), the expected relationship between perspective-taking and relationship satisfaction was not supported by our findings. Instrument choice may account for this discrepancy as Rowan et al. (1995) and Long et al. (1999) used a measure of general empathy, whereas the present study used a measure of empathy expressed explicitly in romantic relationships. Findings from the current study demonstrate a link between only empathic concern and relationship satisfaction, suggesting that perhaps the emotional component of dyadic empathy plays a more important role in relationship satisfaction than its cognitive component, at least when it is considered specifically within the context of romantic relationships. This pattern could arise because simply understanding another’s emotional state is not sufficient to transcend the intimate connection between partners that is required for marital well-being. It may be necessary to enhance intimate connections through actually sharing in the emotional experience of one’s romantic partner.

Consistent with hypotheses, an increase in one’s own dyadic coping significantly enhanced one’s own relationship satisfaction. Several recent studies attest to the positive relationship between these two variables at the actor level (Bodenmann et al., 2001; Bodenmann & Shantinath, 2004; Papp & Witt, 2010; Wunderer & Schneewind, 2008). However, given that much of the existing research has been conducted with clinical samples, this study extends past research by demonstrating a positive association between one’s own dyadic coping and one’s own relationship satisfaction in a community sample.

Partner Effects

In addition to the individual characteristics or personality traits that each individual brings to the relationship, the patterns of interactions and behaviours exchanged within a couple also play a fundamental role in determining the quality and outcomes of the relationship (Kenny et al., 2006). Although it was hypothesized that partner effects would be present in the associations between dyadic empathy, dyadic coping, and relationship satisfaction, results indicated only two significant partner effects in the association between dyadic empathy and dyadic coping. More specifically, empathic concern in women and perspective-taking in men was shown to improve their partners’ dyadic coping strategies. This partner effects may reflect findings that men are usually more comfortable if issues are negotiated from a rational, logical, and unemotional perspective, whereas women choose to focus on their emotional reactions to problems (Ickes, 1993; Kelley et al., 1978). In other words, there is a tendency for men to be more cognitive and for women to be emotional. So it is therefore possible that, when individuals act in a way that is consistent with their partner’s expectations (i.e., when men embody the cognitive component of empathy and women embody its emotional component), the partner will be more confident in their ability to cope with the stressful situation at hand.

Contrary to our hypotheses, no partner effect was found between dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction, or between dyadic empathy and relationship satisfaction. This lack of partner effects is particularly unexpected given that one’s own dyadic empathy (Davis & Oathout, 1987) and one’s own dyadic coping (Bodenmann et al., 2006; Papp & Witt, 2010) has previously been linked to the partner’s relationship satisfaction. These results suggest that one’s own dyadic coping and dyadic empathy do not seem to be good predictors of the partner’s relationship satisfaction. This tendency for more actor effects than partner effects could reflect the findings which suggest that an individual’s dyadic functioning is more strongly related to their own emotions, thoughts, and behaviours (in this case, their own dyadic empathy and coping; Péloquin, Lafontaine, & Brassard, 2011), especially when contrasted with their partner’s relational factors (e.g., Knobloch & Theiss, 2011).

Mediating Role of Dyadic Coping

The hypothesis that both one’s own and the partner’s dyadic coping processes would mediate the association between dyadic empathy and relationship satisfaction was partially confirmed in men. The link between one’s own empathic concern and one’s own relationship satisfaction was only partially mediated by one’s own dyadic coping in men. This finding suggests that the emotional component of empathy generates increased relationship satisfaction in part because the intuitive capacity to share an emotional response one is feeling by putting oneself in one’s shoes acts directly on dyadic coping strategies and behaviours. The fact that the mediation was only significant in men suggests that the association between the emotional component of empathy and relationship satisfaction is mediated by different constructs in men and women.

In addition, there was no evidence of the mediating role of dyadic coping in the associations between dyadic empathy and relationship satisfaction at the dyadic (partner) level. Despite the fact that both dyadic empathy and dyadic coping have been associated with relationship satisfaction in their own way, it would seem that dyadic empathy does not work through dyadic coping to influence relationship satisfaction at the dyadic level. This suggests that either there is no overall effect to mediate or that the association between dyadic empathy and relationship satisfaction may be better explained by factors other than dyadic coping. For instance, an abundance of individual- and relationship-level variables have been associated with relationship satisfaction, including affect and patterns of interaction (see Gottman & Notarius, 2000), as well as the content of cognitions (e.g., Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 1996). Other potential mediators may include prosocial behaviours and interpersonal aggression as both have been associated with empathy (e.g., Graziano, Habashi, Sheese, & Tobin, 2007; Miller & Eisenberg, 1988). These variables may better explain how dyadic empathy could work through dyadic coping to influence relationship satisfaction at the dyadic level, as well as at the individual level for women.

The present study contributes to knowledge on dyadic empathy and its link to dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction both on the individual- and dyadic-level in a sample representative of the stable-couple community. From a clinical standpoint, the findings of the present study suggest working directly on tangible variables (i.e., dyadic empathy and dyadic coping) in order to improve one’s own relationship satisfaction, as well as increasing one’s own dyadic empathy in order to improve one’s partner’s dyadic coping. Couple therapy approaches have become increasingly focused on such variables to gain insight into how coping and empathy impact the quality and stability of romantic relationships (Bodenmann & Randall, 2012; Péloquin, Lafontaine, & Brassard, 2011). If future studies build upon the limitations of the current study by, for example, using a longitudinal design or a multi-method approach, such findings could inform prevention programs by raising awareness about and enhancing dyadic empathy and dyadic coping given their positive effect on relationship satisfaction. Gender specific dyadic empathy enhancement programs, with a focus on increasing perspective-taking in men and empathic concern in women, could also be used to improve dyadic coping in one’s partner.

Limitations and Future Directions

Like all studies, some limitations need to be noted. First, results based on correlational analyses make it impossible to conclusively establish a causal relationship between the variables in question, or to rule out third-variable explanations (Rempel, Ross, & Holmes, 2001). Along these same lines, this cross-sectional design also limits the causal interpretation of the mediational results. Longitudinal studies are needed to address such issues of causality. Second, a multi-method approach that includes more objective measures than self-report questionnaires may provide a better understanding of the relevant concepts and further inform the nature of the associations between dyadic empathy, dyadic coping, and relationship satisfaction. For example, observational measures and interview methods would help to expand current conceptualization of the behavioural variables at play in such interactions.

Prospective studies should nevertheless seek to examine the broader applicability of this model to other dyads, including same-sex couples, which would provide evidence for its validity in a wider range of couples. Future studies should also include additional mediators (e.g., social support, conflict resolution, and communication skills) of the association between dyadic empathy and relationship satisfaction, and examine these with longitudinal data from at least three time points in order to better verify the mediational process (Brassard, Lussier, & Shaver, 2009).

Conclusion

Overall, our findings highlight the complex associations between dyadic empathy, dyadic coping, and relationship satisfaction within a mediational actor-partner interdependence model. More specifically, our findings replicate previous studies supporting the association between one’s own dyadic coping and one’s own relationship satisfaction. Moreover, this study extends past research by demonstrating: 1) an association between one’s dyadic empathy and one’s dyadic coping, and 2) the mediating role of one’s own dyadic coping in the association between one’s own empathic concern and one’s own relationship satisfaction in men. This study also informed dyadic associations, whereby men’s perspective-taking and women’s empathic concern significantly improved their partners’ dyadic coping strategies.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (