Suicidology research has demonstrated that interpersonal dysfunction plays a key role in why people desire death by suicide. Specifically, there are two well-known theories of suicidal behavior that focus on interpersonal connection. Early theoretical work by Émile Durkheim discussed social connectedness as a potential reason for societal suicide rates. This work was ground breaking as previous discussions of suicide focused on an individual’s internal drives and motivations for death. More recently, the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (ITS; Joiner, 2005) sought to provide a framework for understanding suicide by placing theoretical and empirical focus on two interpersonal risk factors for suicidal desire. This theory posits that when feelings of thwarted belongingness (extreme feelings of social isolation and a lack of caring from others) and perceived burdensomeness (belief that one’s existence burdens others) are experienced in tandem, an individual is at-risk of developing the desire to die by suicide. Additionally, research has supported loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for suicidal thinking and behavior (Joiner et al., 2002; Wyder, Ward, & Leo, 2009). Although previous research demonstrates a strong association between interpersonal dysfunction and suicide, little work has investigated the role humor styles play in the experience of the desire for suicide. This is a key oversight, as humor styles have been associated with important interpersonal constructs, such as isolation, social competence, and shyness (Fitts, Sebby, & Zlokovich, 2009; Martin, 2007; Martin, Puhlik-Doris, Larsen, Gray, & Weir, 2003).

Self-defeating humor style may play a particularly pernicious role in suicidal thinking. Martin and colleagues (2003) define a self-defeating humor style as the consistent use of self-disparaging humor employed to strengthen social bonds. The self-defeating humor style entails the highlighting of one’s perceived flaws and weaknesses through ingratiating humor within a social context. This is done in order to be perceived positively in social interactions and to facilitate social bonds. Although its use is intended to be affiliative in nature, this particular humor style is related to various negative interpersonal and intrapersonal concerns.

Generally, research has supported a positive relationship between a self-defeating humor style and negative mental health outcomes. Self-defeating humor has been positively associated with self-reported depression, anxiety, symptoms of social anxiety, feelings of hostility, and general bad mood (Martin et al., 2003; Tucker, Judah, et al., 2013). Similarly, Martin and colleagues (2003) demonstrated a negative correlation between the humor style and self-esteem. This study also demonstrated that self-defeating humor is related to interpersonal dysfunction, including a lack of social intimacy and satisfaction. Personality variables, such as sociotropy and autonomy, which increase susceptibility for depression and suicide, have also been linked to the use of a self-defeating humor style (Frewen, Brinker, Martin, & Dozois, 2008). Although research has demonstrated a clear association between self-defeating humor and known predictors of suicidal thinking, little work has focused on a potential relationship between self-defeating humor and suicidal ideation.

To the authors’ knowledge, only one study has explicitly demonstrated a connection between self-defeating humor and suicidal thinking. In this study, the relationship between the interpersonal predictors of suicide, as outlined by the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (i.e., perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness; Joiner, 2005), and suicidal ideation was strengthened in the presence of a self-defeating humor style (Tucker, Wingate, O’Keefe, Slish, et al., 2013). Additionally, results illustrated positive correlations between self-defeating humor and suicidal ideation, thwarted belongingness, and perceived burdensomeness. Tucker, Wingate, O’Keefe, Slish, and colleagues (2013) theorized that this humor style may be affiliated with suicidal thinking because when a person is frequently disparaging themselves, their flaws and weaknesses are repeatedly identified in social situations. The laughter of others may be perceived as validating these flaws and weaknesses, and could create a sense of social disconnection. Thus, self-defeating humor may be a means of ruminating in an interpersonal context as rumination encompasses consistent focus on one’s distress.

Although multiple definitions and theories of rumination exist, the Response Styles Theory (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991) of rumination is most often studied in relationship to suicide (for a review, see Morrison & O’Connor, 2008). The Response Styles Theory posits that rumination involves the constant devotion of one’s cognitive efforts to the causes and consequences of current distress. Although those who ruminate may utilize this cognitive style to understand their distress, Nolen-Hoeksema (1991) argues that rumination prevents these individuals from adaptively coping with and engaging in activities that will remedy their distress. A ruminative response style has been closely connected to suicidal ideation in studies employing both cross-sectional and longitudinal methodologies, as well as in clinical and community samples (Eshun, 2000; Fairweather, Anstey, Rodgers, Jorm, & Christensen, 2007; Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007; Morrison & O’Connor, 2008; Smith, Alloy, & Abramson, 2006; Tucker, Wingate, O’Keefe, Mills, et al., 2013). Given that both rumination and self-defeating humor have been related to negative outcomes including suicidal thinking, depression, anxiety, and interpersonal dysfunction, research is needed to elucidate the possible relationship between the humor style and cognitive style. Although the use of self-defeating humor may be considered an interpersonal process while rumination is an intrapersonal process, both are conceptually related. Rumination and self-defeating humor both serve the function of consistently focusing on current distress and negative self-focus with an emphasis on highlighting and presenting negative self-views.

Rumination, as defined by Response Styles Theory, is comprised of two specific sub-components: brooding and reflection. Brooding consists of dwelling on negative consequences of current distress (Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003). It has been closely linked to symptoms of anxiety and depression (Fresco, Frankel, Mennin, Turk, & Heimberg, 2002; Treynor et al., 2003). Importantly, brooding is also associated with suicidal ideation, and has predicted suicidal thinking prospectively (Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007; O’Connor & Noyce, 2008). The second component of rumination, reflection, consists of cognitive effort focused on understanding current distress. This style of thinking is enacted in order to evaluate methods of relieving distress (Treynor et al., 2003). The relationship between suicidal thinking and reflection is unclear in the literature. Some research has demonstrated a positive association between reflection and suicidal ideation (Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007; Tucker, Wingate, O’Keefe, Mills, et al., 2013). However, other studies suggest that reflection may be somewhat protective against suicide (Crane, Barnhofer, & Williams, 2007). Yet, other findings have demonstrated a non-significant relationship between reflection and suicidal thinking (O’Connor & Noyce, 2008).

The current study investigated whether rumination and its sub-components, brooding and reflection, are related to self-defeating humor, as well as suicidal thinking. It may be that self-defeating humor serves as an interpersonal mechanism of focusing on negative views of the self and understanding and dwelling on current distress. Individuals who use self-defeating humor keep their weaknesses and flaws (distressful concepts by nature) in focus when interacting socially. Jokes and humorous anecdotes could potentially serve as vehicles for the constant focus and brooding on one’s current distress and perceived weaknesses. Similarly, people may use this type of humor to understand their distress through the reactions of others. Ruminators may seek either validation or disagreement in response to jokes about their weaknesses in order to help understand their distress, as well as to understand how others perceive their distress. Thus, individuals who are likely to engage in the cognitive style of rumination may be predisposed, or more likely to use self-defeating humor as their dominant humor style. Understanding this relationship may provide an avenue toward better understanding the impact of reflection and brooding on current distress during interpersonal interactions.

The broad aim of the current study was to determine whether self-defeating humor style is associated with specific aspects of rumination and suicidal ideation. It was hypothesized that rumination, brooding, and reflection would individually positively predict self-defeating humor. Additionally, it was hypothesized that self-defeating humor style would be positively correlated with suicidal ideation, as seen in previous research (Tucker, Wingate, O’Keefe, Slish, et al., 2013). Finally, it was hypothesized that rumination and its sub-components (i.e., brooding and reflection) would be associated with suicidal ideation through the mechanism of self-defeating humor. The cognitive style of rumination would likely predispose individuals to use self-defeating humor and thus increase their risk for suicidal thinking. In other words, self-defeating humor would have an indirect effect on (i.e., mediate) the relationship between the rumination and suicidal ideation.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants from a large Midwestern university located in the United States were recruited through undergraduate courses and received course credit for their participation. All self-report questionnaires were completed in an online format. The sample consisted of 365 participants, 241 (65.6%) females and 124 (34.4%) males. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 46 years, with a mean age of 19.61. Two hundred and ninety (79.5%) participants identified as Caucasian, 25 (6.8%) as American Indian, 18 (4.9%) as African Americans/Black, 14 (3.8%) as Asians/Asian American, eight (2.2%) as Hispanics/Latino, eight (2.2%) as biracial, one (0.3%) who identified as other, and one (0.3%) who declined to state their ethnicity.

Measures

Demographics Questionnaire

Participants completed a demographics questionnaire that contained questions regarding age, sex, and ethnicity.

Humor Styles Questionnaire (HSQ; Martin et al., 2003)

The full HSQ contains 32 items that measure four humor styles: affiliative, enhancing, aggressive, and self-defeating. Self-defeating humor was the central focus for this study. Items such as “I let people laugh at me or make fun at my expense more than I should,” and “I will often get carried away in putting myself down if it makes my family or friends laugh” are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). The self-defeating subscale of the HSQ contains 8 items, and demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in the current study (α = .79).

Hopelessness Depression Symptom Questionnaire-Suicidality Subscale (HDSQ-SS; Metalsky & Joiner, 1997)

The Hopelessness Depression Symptom Questionnaire-Suicidality Subscale is a four item self-report measure designed to assess suicidal ideation. The questionnaire is part of a larger measure that was designed to assess hopelessness depression. Items on the questionnaire assess the severity and frequency of suicidal ideation within the past two weeks. Responses on the items range from 0 to 3 with each number representing a separate and varying item response. Scores on the scale range from 0 to 12, where higher scores indicate elevated levels of suicidal ideation. Previous research has found the subscale to have adequate reliability (Joiner & Rudd, 1996). The HDSQ-SS demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the current study (α = .95).

Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991).

The RRS from the Response Styles Questionnaire is a 22-item self-report measure of an individual’s overall tendency to ruminate as well as engage in specific sub-components of rumination such as brooding and reflection. Responses are measured on a 4-point Likert scale, and range from 1 (almost never), to 4 (almost always). The brooding subscale of the RRS consists of five items, such as, do you generally “Think ‘what am I doing to deserve this?” The reflection subscale also consists of five items, such as, do you generally “Go away by yourself and think about why you feel this way.” The overall RRS demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = .95). The five-item subscale of reflection exhibited good internal consistency (α = .85), and the brooding subscale also exhibited good internal consistency (α = .85).

Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of study variables are presented in Table 1. Results of correlation analyses provided support for the first hypothesis. Namely, zero-order correlations demonstrated that self-defeating humor was positively associated with both suicidal ideation and total ruminative style. Similarly, self-defeating humor was positively associated with the ruminative sub-components of brooding and reflection. Total rumination, brooding, and reflection were also positively correlated to suicidal ideation, which was expected given previous research findings.

Table 1

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlation Coefficients of Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-defeating | - | ||||

| 2. Rumination | .21* | - | |||

| 3. Reflection | .17* | .86* | - | ||

| 4. Brooding | .19* | .91* | .72* | - | |

| 5. Ideation | .17* | .37* | .30* | .31* | - |

| M | 27.83 | 37.77 | 8.05 | 9.18 | 4.21 |

| SD | 8.57 | 13.68 | 3.33 | 3.57 | 1.02 |

Note. Self-defeating = Humor Styles Questionnaire - Self-defeating Subscale; Rumination = Ruminative Response Scale total; Reflection = Ruminative Response Scale – Reflection Subscale; Brooding = Ruminative Response Scale – Brooding Subscale; Ideation = Hopelessness Depression Symptom Questionnaire – Suicidality Subscale total.

*p < .01.

The second hypothesis sought to examine if self-defeating humor mediated the relationship between rumination and suicidal ideation. For the mediation analysis, total ruminative style served as the independent variable (X), suicidal ideation served as the dependent variable (Y), while self-defeating humor served as the mediator (M). The total, direct, and indirect effects were estimated using the nonparametric bootstrapping procedure described by Preacher and Hayes (2008) with 1,000 bootstrapping samples. For the current analysis, the INDIRECT macro for SPSS was utilized (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

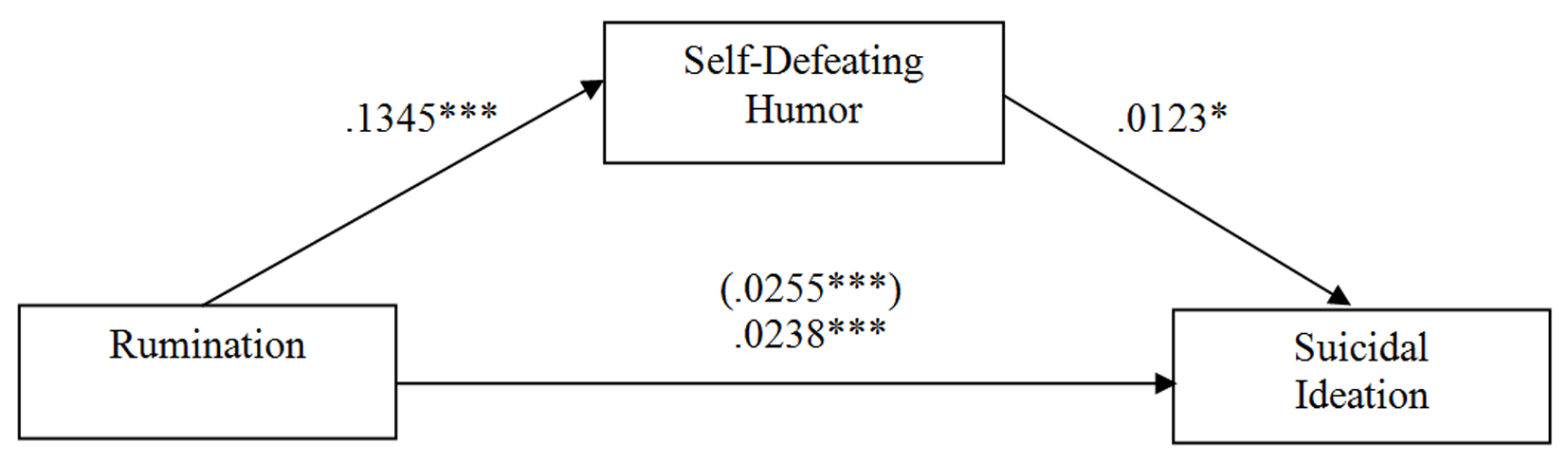

Results for this hypothesis are displayed in Table 2, and a pictorial display of the pathways for the analyses is displayed in Figure 1. Bootstrapping estimates revealed that self-defeating humor style had a significant indirect effect on the relationship between total ruminative style and suicidal ideation. More specifically, the total (path c) and direct effects (c’ path) of total ruminative style on suicidal ideation were .0255, p < .01 and .0238, p < .01, respectively. The difference between the total and direct effect was different from zero based on the point estimate of .0017 and a 95% Bias Corrected and Accelerated (BCa) bootstrap CI of .0005 to .0041. These findings are consistent with the interpretation that greater use of an overall ruminative cognitive style may lead to more usage of a self-defeating humor style which may, in turn, lead to higher levels of suicidal ideation.

Figure 1

Model of the indirect effect of overall rumination on Suicidal Ideation through Self-Defeating Humor.

Note. Numerical values are the unstandardized regression coefficients and the number in parentheses represents the unmediated path.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Table 2

Indirect Effects of Ruminative Cognitive Styles on Suicidal Ideation Through Self-Defeating Humor

| Indirect Effects | Point Estimates | Bootstrapping

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product of Coefficients

|

Percentile CI

|

BC 95% CI

|

BCa 95% CI

|

||||||

| SE | Z | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| RRS Total | .0017 | .0009 | 1.897 | .0004 | .0161 | .0005 | .0036 | .0005 | .0041 |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Brooding | .0066 | .0032 | 2.044 | .0015 | .0136 | .0020 | .0152 | .0023 | .0163 |

| Model 3 | |||||||||

| Reflection | .0065 | .0032 | 2.022 | .0016 | .0137 | .0021 | .0164 | .0023 | .0171 |

Note. Confidence intervals containing zero do not represent a significant difference from zero. BC, bias corrected; BCa, bias corrected and accelerated; 1,000 bootstrap samples.

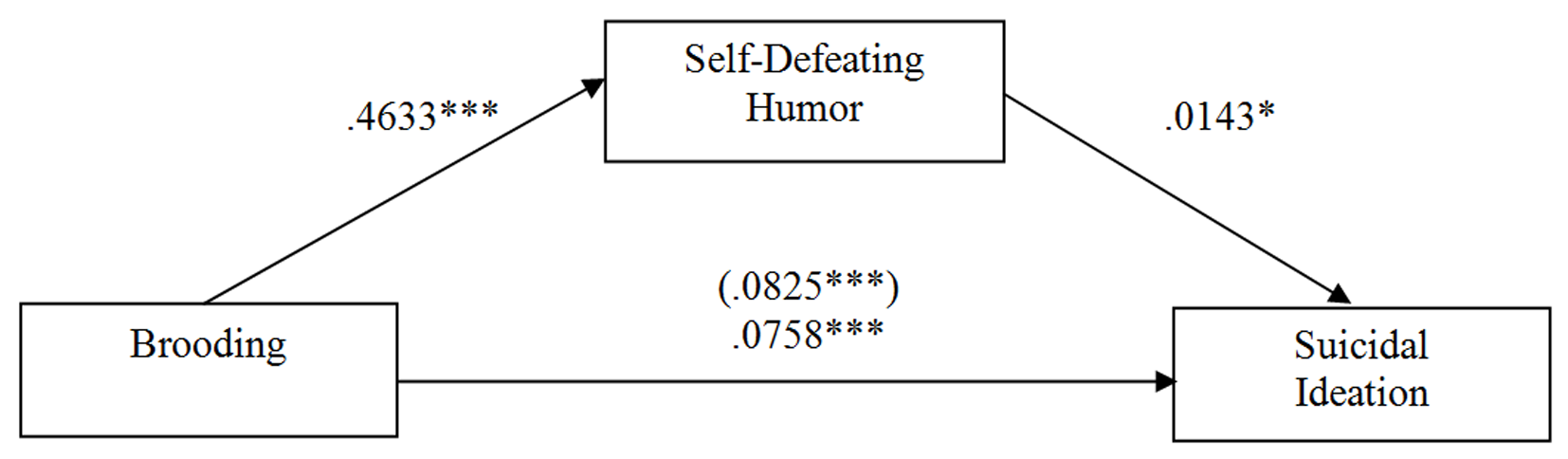

Because total ruminative style consists of two sub-components (e.g., brooding and reflection), which have been linked to psychological dysfunction, it was important to determine if the constructs differed in their direct and indirect effects on suicidal ideation. Therefore, two additional bootstrapping analyses were conducted to determine if either brooding or reflection was driving the effect for the above mediation analysis of total rumination, self-defeating humor, and suicidal thinking. In the second indirect effect analysis, brooding served as the predictor variable (X). Following the mediational model described in the above analysis, self-defeating humor and suicidal ideation served as the mediator (M) and outcome variables (Y), respectively. The total, direct, and indirect effects were again estimated using the nonparametric bootstrapping procedure. Results for these follow-up analyses are displayed in Table 2, and are pictorially depicted in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. Bootstrapping estimates revealed that self-defeating humor style had a significant indirect effect on the relationship between brooding and suicidal ideation. More specifically, the total (c path) and direct effects (c’ path) of brooding on suicidal ideation were .0825, p < .01 and .0758, p < .01, respectively. The difference between the total and direct effect was different from zero based on the point estimate of .0066 and a 95% Bias Corrected and Accelerated (BCa) bootstrap CI of .0023 to .0163, yielding a significant indirect effect. These findings are consistent with the interpretation that greater use of brooding ruminative style may lead to more usage of a self-defeating humor style which may, in turn, lead to higher levels of suicidal ideation.

Figure 2

Model of the Indirect Effect of Brooding on Suicidal Ideation through Self-Defeating Humor.

Note. Numerical values are the unstandardized regression coefficients and the number in parentheses represents the unmediated path.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

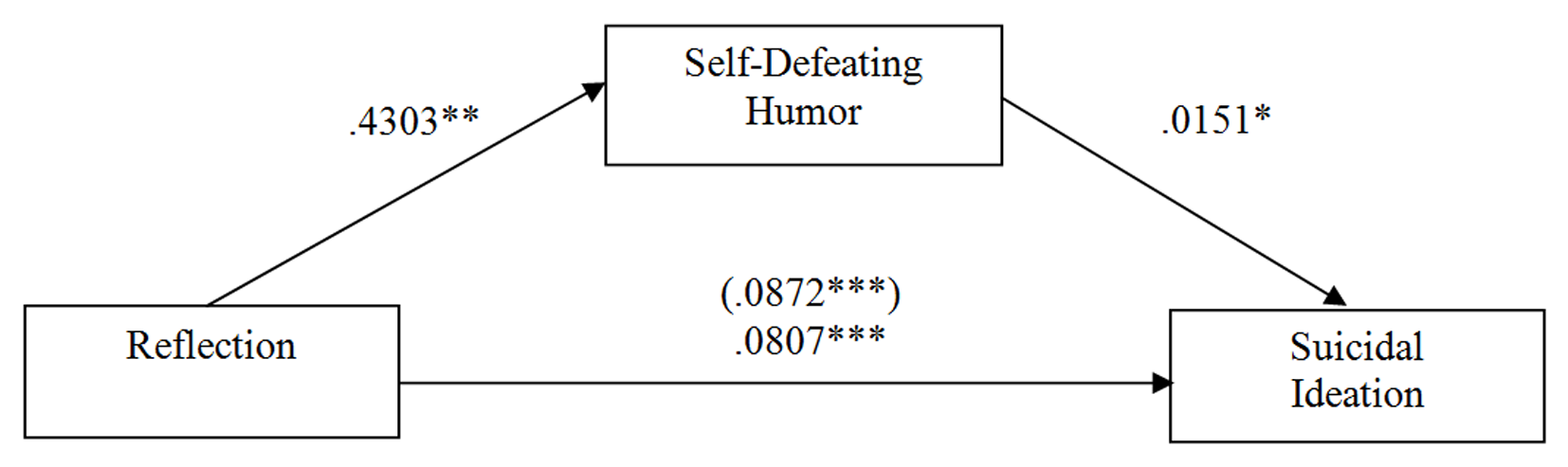

Figure 3

Model of the Indirect Effect of Reflection on Suicidal Ideation through Self-Defeating Humor.

Note. Numerical values are the unstandardized regression coefficients and the number in parentheses represents the unmediated path.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

For the final analysis, bootstrapping estimates also revealed that self-defeating humor style had a significant indirect effect on the relationship between reflection and suicidal ideation. More specifically, the total (c path) and direct effects (c’ path) of reflection on suicidal ideation were .0872, p < .01 and .0807, p < .01, respectively. The difference between the total and direct effect was different from zero based on the point estimate of .0065 and a 95% Bias Corrected and Accelerated (BCa) bootstrap CI of .0023 to .0171. These findings are consistent with the interpretation that greater use of a reflective ruminative style may lead to more usage of a self-defeating humor style which may, in turn, lead to higher levels of suicidal ideation. Overall, analyses revealed a significant indirect effect of self-defeating humor style on the relationship between rumination and suicidal ideation, as well as the two sub-components of rumination (brooding and reflection) and suicidal ideation individually.

Discussion

Recent research has suggested a relationship between employing a self-defeating humor style and an increased risk for suicide (Tucker, Wingate, O’Keefe, Slish, et al., 2013). The current study further explored this relationship by investigating how self-defeating humor may relate to ruminative cognitive style, a common predictor of suicidal thinking (Morrison & O’Connor, 2008). Because previous research has identified both intrapersonal and interpersonal processes as fundamental in the development of suicidality (Joiner et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2006; Wyder et al., 2009), rumination and its relationship with self-defeating humor was conceptually important to investigate in relation to suicidal ideation. The current study proposed that utilization of both self-defeating humor and ruminative responses may behaviorally serve to create, reinforce, or refute intrapersonal and interpersonal distress, placing individuals who employ both self-defeating humor and a ruminative response style at high risk for suicidal thinking.

Correlational results supported study hypotheses. Self-defeating humor style was positively associated with rumination and suicidal ideation. This supports previous findings on the relationship between self-defeating humor and suicidal ideation (Tucker, Wingate, O’Keefe, Slish, et al., 2013). Self-defeating humor was also positively associated with brooding and reflection as well as the larger construct of rumination. While previous findings of the reflective component have been mixed, these results lend credence to the negative aspects of both brooding and reflective rumination styles.

Results also supported the hypothesis that rumination would be related to suicidal ideation indirectly through self-defeating humor. Results of a bootstrapping analysis supported an indirect effect for overall rumination and suicidal ideation through self-defeating humor style. This result supports previous research illustrating a significant direct relationship between the use of a ruminative cognitive style and suicidal ideation; however, there may also be an indirect effect between ruminative cognitive style and suicidal ideation when individuals utilize a self-defeating humor style. The cognitive style of rumination may predispose individuals to use more self-defeating humor and thus be at an increased risk for suicidal ideation. Through both intrapersonal and interpersonal processes, individuals may maintain or exacerbate their suicidal thinking.

Because the results demonstrated a significant indirect effect for self-defeating humor, it was conceptually important to examine both brooding and reflection. Both of the sub-components address important and theoretically different aspects of rumination, yet they remain part of the larger conceptualization of rumination. Final results yielded a significant indirect effect for brooding and reflection. Individuals who tend to brood may be more likely to engage in the use of self-defeating humor as an outlet for their distress. Individuals who continually reflect on their distress may likely use self-defeating humor as a way of understanding the causes, consequences, and potentially the validity of their issues. In both of these processes, the analyses suggest that both brooding and reflection may lead to more usage of a self-defeating humor style which may, in turn, lead to higher levels of suicidal ideation.

The results of the current study illustrate a close link between self-defeating humor and rumination. This relationship was expected as both self-defeating humor style and rumination have intrapersonal elements and entail, and likely exacerbate negative views of the self. Consistent focus on distress and perceived weaknesses and flaws through both rumination and disparaging joke telling likely are influenced by and contribute to feelings of low self-worth and self-esteem. Similarly, self-defeating humor style may serve as an interpersonal means of ruminating. Those who use this humor style consistently recollect their weaknesses and faults through telling disparaging jokes about themselves. Such disparaging jokes may be used as an interpersonal means to brood on and/or better understand their distress (a process which consumes their cognitive efforts) through the reactions of others. Behaviorally, jokes elicit reactions and responses that might otherwise be masked by individuals, thereby providing bolstering or refuting information to the ruminating individual. Similar to rumination, the use of self-defeating humor may then keep individuals from moving into the active phase of coping. Instead of seeking out social support or partaking in problem-solving and proactive behaviors that may decrease their thoughts of suicide, individuals prone to self-defeating humor use may continue to focus on perceived weaknesses and faults through their joke telling. This sustained cognitive effort toward flaws may then exacerbate or maintain their distress and thoughts of suicide.

Take for example a person making a self-defeating joke regarding his or her physical appearance. This individual may ruminate about the causes and consequences of his or her attractiveness. The self-defeating joke may have initially been intended to strengthen social bonds; however, it may actually increase distress through deploying more cognitive resources toward the concern. Similarly, laughter from close others following this joke may be perceived as evidence that he or she should indeed be concerned about his or her appearance. This perceived evidence is akin to the reflection sub-component of rumination. Specifically, the individual may have attempted an internal (turned external; joke) problem-solving strategy (to gain evidence of their control over their distress) which was refuted by the behavioral feedback from others after engaging in self-defeating humor. On the other hand, a close other who responds to this joke with a comment about how the ruminative individual’s appearance does not look “bad” may challenge the distress. Through either the perceived validation of the distress (i.e., laughter) or the challenging of the distress (i.e., through a comment about the inaccuracy of the joke), the individual may continue to engage in the process of passively comparing their current situation with an unachieved standard. In this case, the individual broods over the unachieved standards of distress reduction after the use of a seemingly bond-strengthening initial joke. Akin to the mediational results, the use of a ruminative cognitive style may be associated with increased distress (suicidal ideation) indirectly through the use of self-defeating humor.

Along with demonstrating a relationship between self-defeating humor and rumination, study results have potentially important theoretical implications for the broader depression symptomology literature. It may be that self-defeating humor and rumination not only contribute to suicidal ideation directly through each other but also through increasing the severity of symptoms of depression. Like suicidal thinking, rumination and self-defeating humor have closely been linked to symptoms of depression (Martin et al., 2003; Michl, McLaughlin, Shepherd, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2013; Tucker, Wingate, O’Keefe, Slish, et al., 2013). It may be that the negative self-focus of both rumination and self-defeating humor encourages and exacerbates symptoms of depression in individuals who are not experiencing suicidal thinking. As depressive symptoms have been related to interpersonal consequences (Joiner & Metalsky, 1995), the increased incidence of depressive symptoms and their interpersonal consequences resulting from rumination and self-defeating humor use may place individuals at a heightened risk for suicidal thinking.

Additionally rumination and self-defeating humor may increase suicide risk through their contribution to and maintenance of interpersonal risk factors of suicide. Recent research supporting the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Joiner, 2005) has indicated that the desire for suicide likely develops through feelings of extreme social disconnection (thwarted belongingness) and a belief that one is a burden to others (perceived burdensomeness; Joiner et al., 2009). Like suicidal thinking, the use of self-defeating humor has been empirically associated to feelings of loneliness and lack of social support (Dyck & Holtzman, 2013; Hampes, 2005). It is reasonable to posit that the use of this humor style may also contribute to feelings of thwarted belongingness. Self-defeating humor may lead to increased suicidal thinking by way of increasing feelings of loneliness, social rejection, and thus thwarted belongingness.

Similarly, self-defeating humor and rumination may likely exacerbate feelings of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness and their influence on suicidal thinking. Tucker, Wingate, O’Keefe, Slish, and colleagues (2013) demonstrated that a self-defeating humor style strengthened the relationship between suicidal thinking and both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. It may be that those with a ruminative cognitive style who are experiencing feelings of thwarted belongingness and/or perceived burdensomeness utilize self-defeating in an attempt to cope. However, this humor use conversely exacerbates the feelings of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness because self-defeating humor use entails a negative self-focus, consistent attention to perceived weakness and flaws, and possible social rejection.

Although the current study sheds light on the relationship between rumination, self-defeating humor, and suicidal ideation, no study is without limitations. The use of a cross-sectional study design is a limitation of the current study. Due to this methodology, evidence for causal relationships and temporal associations of variables being examined cannot be inferred. A longitudinal design would allow for a better understanding of how self-defeating humor and rumination are related, and how these variables temporally relate to thoughts of suicide. Another limitation is the use of an undergraduate convenience sample, where the base rate of suicidal behavior is relatively low compared to clinical or community samples. Similarly, the sample was ethnically homogenous, and most of the participants identified as Caucasian. Future research would be prudent to include samples with higher base rates of suicidal ideation, such as a treatment-seeking population, as well as more heterogeneous samples with regard to ethnicity, age, and other demographic characteristics to determine improved generalizability of study results.

Clinical implications from the results of this study can be drawn and extended to clinical work and future research. Primary clinical assessment of suicidal behavior in at-risk clients may be supplemented by a secondary assessment of engagement in ruminative cognitive styles and self-defeating humor. Clinicians may target the use of a self-defeating humor style and focus on rumination by engaging in empirically supported treatments, such as Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Focusing on identification of maladaptive behaviors, such as disparaging joke-telling and cognitions may help the client to reduce their psychological distress and suicidality. Additionally, teaching clients alternative problem-solving strategies and social skills can help them strengthen interpersonal relationships and adaptive coping mechanisms. Overall, the current study provides important knowledge about an additional aspect of an interpersonal dysfunction, self-defeating humor, in relation to rumination and suicidal ideation.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (