Formative Journeys Into Creative Drama

Playing in a Supportive Atmosphere

Laura: I was born in Gilbert Minnesota in 1935 during the height of the depression. We moved to Wisconsin to the farm where my mother grew up. As a child, theatre meant pretend and acting. I put on little plays for my Great Aunt Mame when she came to visit. The blanket went up on the clothes line and our humble front yard on a little farm in Wisconsin became anywhere I wanted it to be through the magic of theatre. Aunt Mame paid me five cents per performance. I told my mother when I was seven that I wanted to become an actress when I grew up. In high school I devoted myself to music but always kept my interest in acting.

Zayda: I was born in 1957 close to Medellin and grew up in a farm where we did not have television. Contrary to what young people might think today, we were not bored. With siblings, cousins or neighbors, I spent weekends or vacations creating stories, using my mother’s sheets and clothes as our costumes and the house furniture as our imaginary scenery. At that time, we had long school days, so some classmates and I had a good time at recess improvising stories and performing them in special occasions. This is very different from what students experience today: at home, they spend hours and hours in front of the television and rarely have opportunities to play with friends at school because of the drastic reduction of recess time.

Playing and Learning as Young Adults

Laura: When I went to undergraduate studies I found out what music had to offer me and I should not deny my natural calling to be in theatre. Theatre matched my personality. In theatre I could be anyone. I could study history, literature, psychology, music, the visual arts, throw myself into any passion—all in the name of work. And I would always be with other interesting people drawn to this art. I learned how to make costumes, sets, do lighting, loving every aspect of the art. My first goal was to become a high school English and theatre teacher, which I did for 6 years. I learned to love my students and after directing about 15 plays, I was getting skilled at it. The work of Viola Spolin (1963) became important in my own work, and I found improvisation challenging and useful as I worked with everyone from pre-schoolers to senior citizens.

Zayda: When doing my studies in B.A. in Education, I was uneasy with the traditional role of what was expected of me as a teacher: one who plans the contents and activities of a class while children obediently follow his or her orders. I saw in theatre an opportunity to develop creative alternatives for education. Lacking Schools of Dramatic Arts at that time I got involved in some theatre troupesi, which were part of The Latin America Theatre movement of the late 1970s based on collective creation: the actors’ active participation in the research, creation and production of the plays and the audience involvement during the performance (Garzón Céspedes, 1978; Luzuriaga, 1978). Independent theatre was also one of the few alternatives young people had to engage in critical analysis of political situations in the search for social transformation of a very unequal society.

Thinking About Education Through Theatre

Laura: In the early 1960's, after I had taught English and speech in high schools for seven years and had earned my MA degree, I took a course in creative dramatics at a nearby university. I had always delighted in children and wanted to learn how I could combine pretend and theatre with them. The course I took was dissatisfactory. I had been working with children for many years. It was obvious that the male professor had not taught the drama he was trying to teach us. I decided to find out about how to do creative dramatics through my own experiments. I came to understand Creative Drama as an improvisational art form led by an adult for children, young people, and adults. It is characterized by action, character, thought or theme. Often the leader and the participants have a goal they hope to reach in the acting out of the theme. I acknowledge that other terms are often used to describe this activity: child drama, creative dramatics, and improvisational theatre are a few. I feel more comfortable with the term creative drama.

Shortly after that I was hired to teach at Grand Valley State University and soon developed a course in Child Drama. I began reading everything I could find on the subject and attending workshops throughout the region on theatre and education. Within the university course I brought children into the classroom and the university class went to the schools. I read the works of Englishmen Brian Way (1967) and Peter Slade (1973). These practitioners provided a way of working that gave the children more freedom of expressing their own emotions and interests than I had been exposed to before. In the work of American creative dramatics, play was usually based on children's literature and lead by a teacher with a strong hand. I regret that I did not think to make a record of these experiments in children's performance, development and problem solving, contrasting various methods. I know of no one who was doing that at the time. Now our field is much more research based and there is work studying these questions.

I needed to know more so I earned a Ph.D. in theatre at the University of Michigan where Shakespeare was the central emphasis. I was lucky to learn to write well there and wrote an award winning dissertation on the beginnings of professional theatre for children in the United States (Salazar, 1984). At Grand Valley State University I developed the Theatre Program. I also married and had two children. Their love of pretend mirrored mine. I continued playing and experimenting with varied groups in schools and my community.

Zayda: When invited to marginalized urban and rural localities, our theatre troupe had to perform outdoors, in playgrounds or plazas, because there were not proper auditoriums; therefore children were the first audience that came to see us. However our plays were too serious and boring for them to enjoy so we decided to stage theatre plays specially oriented to them. Gilberto Martínez, one of the New Theatre leaders in Colombia, introduced us to Viola Spolin’s work on improvisation, which helped us to recover the playful part of ourselves. We kept exploring social content in our plays, adding music, color and humor as well as having children participate during and after performances. I never enjoyed my work more as an educator interacting with these young audiences. What we were doing is what is known as Theatre for Children; still I wondered how can children themselves express through this art form and how should we as educators enhance self-expression? This brought me to the world of Creative Drama.

Experiencing and Experimenting

Laura: In the 1960’s as a teacher of young men who could be called up to go to Vietnam at any time, I was shocked and horrified at what my beloved country was doing to others and its own. I was young, too, and I wanted to have my teaching and work with young people reflect their deepest feelings. Anti-war demonstrations were going on throughout the country. I lead my students to create happenings and sit-ins and symbolic acts across the campus, bringing attention to this problem. I discovered what moved audiences and what pushed the university administration to their limits. I believed that war was futile, an idea I had held since my dear second grade teacher went off to the Pacific to fight in World War II, and my fourth grade teacher lost her brother to the war. In the fourth grade my teacher found me crying in the cloak room. “Why are you crying, Laura?” she asked. “I hate this terrible war,” was my answer. Theatre was a potent way to express this belief and I directed my students in a production of Lysistrata, as well as improvised pieces.

I started a professional children’s theatre and began to understand how to appeal to children as an audience for theatre. Ever interested in learning more, I became active in professional organizations which expanded my interests and skills through workshops and lectures. Travel broadened my understanding of humanity and I marveled at our similarities and the clever ways other peoples solved the same problems facing all of us. I learned from seeing the practice of theatre in its many forms. I sponged it all up, anxious to hurry home and try out new ideas. As a result of learning, reading and travel, I developed a method on how to use theatre/drama in the classrooms and a university course teaching future teachers through giving them experiences in drama—attempting to pass on the joy of play as well as a respect for its serious content. Somehow it all worked together to make me the practitioner I became: director, acting teacher, child educator, professor, and human being –open to all things that might be shared through the dramatic arts.

Zayda: When finishing my undergraduate studies, I asked the welfare office at Universidad de Antioquia to support an experimental children’s theatre group, which they did. Teatro Bambalinas, as this children’s project came to be known, differed radically from what was practiced as “theater” in the traditional school environment: students’ rote learning of a script to be performed to an audience in schools’ special events, in which the teacher as the director made all decisions. Instead, I invited Bambalinas’ participants to initially engage in social games to help them to interact better with each other and then to improvise play episodes from storybooks or their own ideas, which helped me structuring the script and mise-en-scène. Some artist friends assisted me with the props, music and choreography, always sharing decision making with the children; among them my two own, whom I was lucky to raise in this creative atmosphere while the country was going through a very violent time during the 80sii. The original plays we developed were about situations that were of deep concern for these children, like how to create a more sensitive school environment open to children’s needs and expectations, and how to develop a more just societyiii. Observing how lively and securely these young actors expressed themselves, teachers began to ask me for workshops on children’s expression through this art form. I decided to begin a Masters’ studies in child psychology and continue self-study in creative drama to develop better teaching experiences. Because of my pioneering work in this field I was invited to be part of the academic committee of the newly created B.A. in Childhood Education at Universidad de Antioquia, where I began my life as a professor and wrote my first book: Children’s Integral Development Through Creative Theatre (Sierra, 1985); expressing all my hopes in contributing to a more peaceful and creative country for all our kids, a dream I’m still pursuing.

On their experience in Teatro Bambalinas, here some participants’ comments:

I like to be in theatre for the way they teach us to express ourselves and unveil our imagination (Diana, age 12). I like to dream, laugh and sing, and in our improvisations can do those things. Here my ideas are taken into account, where in other places only adults rule (Alejandra, age 13). I like to be in theatre because I have more friends to talk with, because I like to work in a group and because I feel in a good environment (Felipe, age 9). In each rehearsal we learn new things and grow in hopes to make a happier world. It is a work we do with much love and spirit (Natalia, age 12). We arouse creativity, construct new fascinating worlds, experience new sensations, and develop corporal expression (Isabel, age 13). It is good to know that we always have here a support, a big support, where we can express through improvisations the things we care about, feel and live (Tania, age 14).iv

Maturing and Transforming Careers

Exploring Methods and Styles in Dramatic Arts

Laura: In the early 1980s I met Dorothy Heathcote and went to several of her workshops, learning to use some of her techniques, combining them with my ideas in creative drama. I admired Heathcote’s ability to jump into the drama herself, making herself a part of the drama, someone the children could play with instead of playing for. Her mental agility matched the children’s, and she was able to put them into fascinating situations, drawing out their solutions. Heathcote included conflict and the resolution of conflict in her work. There were no more little bunnies hopping around the field or historical pageants. She used all of the elements of dramatic literature: character, plot, conflict and resolution, with a good bit of Aristotle’s action, language, music and spectacle. She played with time as well. The children became respected makers of serious drama, solving adult problems while keeping the conflict within children's understanding. On the other hand, she might turn to comedy and bring the children into a hilarious farce. Most of all she committed to the drama, making it a serious study of character and action (see Heathcote, 1992). I wanted to be able to do that. My book on this method, Teaching Thematically, Learning Dramatically (Salazar, 1995) became the result of my quest.

Zayda: Wondering about children’s ability to engage in improvising stories from different stimuli, I found out that what we referred to as improvisations in theater is very close to what psychologists describe as children’s symbolic, make-believe, representative, pretend, or dramatic play (Piaget, 1962; Rosenberg, 1987). The element of dramatic play appeared to be the magical clue. Dramatic play seemed to be the link connecting theatrical improvisations and creative drama with the early play of childhood. However, I noticed a huge gap, a kind of a black hole in studies documenting the evolution of dramatic play from preschool to school-aged children. There were many assumptions in the literature that an interest in dramatic play declines as children matured. However, grown-up children, even adults, when offered a socially accepted environment still liked to dress up and create improvised characters and situations, as I was witnessing them doing in the theater Bambalinas. Why is it necessary to stimulate corporal expression and improvisational skills in older children and adults when younger children were so confident at expressing themselves when playing pretend? If I were ever going to be more effective in sharing with teachers the enormous potential of dramatic play, I realized that I needed to improve my research skills to learn how to follow up and evaluate children’s processes when engaging in this activity. Not having graduate studies in childhood education or creative drama at home, I applied for a Fulbright scholarship, which brought me to the Torrance Center for Creative Studies at the University of Georgia in the United States in 1995.

Dramatic Play as the Source for any Dramatic Arts

Laura: I was asked by the American Alliance for Theatre and Education to do a meta-study of dramatic play in order to flesh out our understanding of theatre and children. This evolving national organization in the United States purposely tied what it does in creative drama or child play or whatever name you give it, to the theatre, hoping it would give stature to the field. We hoped universities would include it in their study of theatre, community theatres might begin offering creative drama classes for children, and professional theatres would do the same. We hoped to develop a continuum from infant play to participation in and appreciation of theatre in adults. At the same time, we hoped to connect our field to education, psychology and sociology where children’s play and creativity was being studied. Therefore I and three other writers attempted to review all of the important papers written about social pretend play by child development specialists which had been published in professional journals during a ten year period (Salazar, Berghammer, Brown, & Griffin, 1993). As I looked at this large amount of literature, I kept coming back to my understanding of classical theatre. These scientists were describing the very things Aristotle had found in theatre: plot, character, action, thought, music and spectacle.

Zayda: If dramatic play was considered a leading source of cognitive, linguistic, emotional and creative development by major psychologists, why is this activity not encouraged after the preschool years? During my research I found that despite the importance given to the role of play in children’s development, psychologists agreed in affirming its decline as children mature, explaining this decline as inhibition and transformation into daydreams because of the repressive role of culture (Freud, 1908/1958), children's thinking becomes more adapted to reality (Piaget, 1946/1962), and play evolves into imagination and interiorized thinking (Vygotsky, 1930/1990; Vygtosky, 1933/1976). A contextual reading of these theories into Western concepts of child development provided me a different view. These influential theorists interpreted as "natural" that children went to school at a certain age and engaged less and less in symbolic play as they got older. They took for granted the role and features of schooling in a modern society, in which children (especially children from the working class) are negatively influenced by the many institutional regulations that isolate their time to play from their time to work. Different studies show that in elementary and secondary education, the curriculum emphasizes academics while playgrounds are more oriented to physical activity than to imaginary play (Pellegrini, 1995). Another prejudice against including dramatic play in elementary and secondary education is the cultural bias that play does not contribute to serious learning (Glickman, 1984) and the misconception of play as only entertainment (López Quintás, 1977; Montaña, 1972).

Laura: I concluded that even three and four year old children were dealing skillfully with theatre elements, solving problems and understanding their place in society through their play. Dramatic play had power to help children become better people and create groups to work together well. Why could not dramatic play be used for these purposes with adults? Role-play shares some characteristics with dramatic play, although most adults think role play is rather silly and do not take it as seriously as young children would. It was not until I discovered Augusto Boal (1979) that I found the end of the continuum of play. Boal gave ordinary adults the freedom to solve problems through drama. My book Youth Take the Stage (Salazar, 2010) provides a way for teenagers to use drama to the same purpose and with the same seriousness as a small child might have in his play.

Zayda: I also concluded that contrary to the assumptions that dramatic play declines as children get older, observations from my research in Colombia and the United States showed that older children still enjoy engaging in dramatic play whose complexity and variability grows in relation to: (1) the nature of the interactions among the participants; (2) the nature of the metacommunicative strategies used by participants to suggest and negotiate ideas; (3) the nature of the ideational process involved in the creation of the play-stories; (4) the nature of the content of the play-stories configured through dramatic play (Sierra, 1998).

Finding a Place in the Field for Creative Drama

Laura: I was fortunate to be one of the participants at the organizing meeting of the American Alliance for Theatre and Education (AATE) and continued to be a leader in that organization for the following ten years—1987-1997, serving as its President from 1993-1995. I was also very active in the International Association for Theatre for Youth (ASSITEJ) and the International Amateur Theatre Association (AITA/IATA) and served as its United States President from 1991-1993, editing its newsletter of the Americas for ten years. I also participated in the initial International Drama and Education Association (IDEA) congress in Portugal as it struggled to create a worldwide theatre society—one that would not be Eurocentric. Each one of these organizations in their own way has made me who I am.

Such groups are essential to the development of our field. Even in a large country such as the United States, there are a small number of people scattered over a vast area devoting themselves to the study and practice of theatre for young people. Being active in drama organizations can help us self-correct our practice and remove doubts about the validity of our work. Making contacts and keeping track of colleagues alleviates the loneliness of working in isolation. Professional organizations can provide a unified front to face administrators and politicians who do not understand the value of creative drama and drama’s way of teaching and learning. In the early 1990’s the Congress of the United States passed an educational reform act called No Child Left Behind. This led to the development of National Standards and a universal curriculum for all subjects taught in American public schools. States could accept the standards, modify them or not accept them at all. I served on that committee with great hopes. We did develop a curriculum for drama and even a way to assess student progress. I would like to say that all these efforts drove schools to include drama in their curriculum, but it did not happen. The pendulum swung away from the arts, and today, the struggle to include drama in schools in the United States continues.

Zayda: I learned about the importance of educational associations to impact educational policies when doing my doctoral studies. This gives me the opportunity to honor my major professor, Dr. Mary Frasier, an Afro American leader in the field of gifted education, who devoted her research career toward recognizing and enhancing the gifts and talents of African American children and other underrepresented groups by using alternative approaches to standardized tests, among them dramatics. Through her I became more sensitive in understanding and making visible the needs, interests and expectations of non-dominant groups in my country (Afro, Indigenous, and Peasants), an endeavor I assumed as soon as I went back to my home country.

Crossroads in Kenya

Laura: I came to Kenya full of broad experiences in theatre, creative drama, improvisation, and Shakespeare, with a love for humankind. My passion at that time was in performance art and it was in this area I gave a talk and a workshop, hoping at the same time to sponge up anything Kenya might have to offer. Performance art provided a new way for me to think about the power of player and audience. Performance art crept into my work, as I experimented with fusing creative drama into it. I sought opportunities to test my theories and skill. Events were designed to give the hesitant courage, to bring out feelings long buried inside, to provide opportunities for physical and mental freedom, to move people from isolation into community. Performance Art comes out of visual art and therefore provides a more subtle and broad way of thinking about the communication aspects of performance. Instead of speaking directly or even symbolically, performance artists hope to give the observer the kind of experience one would get in an art gallery or a dream. A performance artist might take a situation and move it around so it could be seen from all sides. In a gallery an observer would walk past a painting or around a sculpture and think, "that reminds me of my girlhood home," or it might call up a dream where one was very frightened. That is the same result the performer expects from the audience, only that the audience will personalize the performance piece and move it into his own daydream, creation, or memory bank. In my work I created situations using props, visions, actions, sounds, and characters that would make memories and daydreams and raise questions about contemporary issues. My book, Making Performance Art (Salazar, 1999) records that journey.

Zayda: I went to present the results of my doctoral research project in the 1998 IDEA Congress in Kenya. There I learned about Dr. Laura Salazar’s work. She also attended my presentation and suggested that I submit it to the best dissertation award sponsored by the American Alliance for Theatre and Education, an organization I did not know at that time. I followed her advice and one year later I flew from Colombia to the 1999 AATE conference in Chicago to receive this award (Sierra, 2000).

Laura: While in Kisumu, the city of the IDEA Congress, Zayda Sierra and I went with a group to the countryside to spend an overnight in a village, staying at a home of a kind young drama teacher. There we met AIDS face to face. Four orphaned teenage relatives lived with the couple. The husband was very thin and very ill. I found out later that he died of AIDS a month after the Congress. In Kisumu my colleague Shirley Harbin and I sat in front of two rows of lively children from a theatre group in Nairobi. They had come to the Congress to perform their play. Their director told us that that they lived at the Good Samaritan Children’s Home in Nairobi’s Mathare slum. All week we talked and laughed with each other. A sweet ten year old girl named Margret liked to sit close to me. Back in the United States, I found out more about the Home and the way these healthy intelligent orphans of AIDS were being raised. I thought about Margaret and how I could help them.

Zayda: Local theatre groups were invited to perform during the IDEA Congress. A group of Maasai men were invited to perform in an open space in Kisumu. With their traditional red capes, they sang and did some storytelling in their tribal tongue, while dancing major events of their life as hunters and shepherds. Another local theatre was a group of teachers who created a collective play to reach rural areas audiences and talk about the risk of HIV/AIDS, an epidemic that had been killing African population at a very fast rate. I was very moved to see theatre as an educational tool in areas where information through TV and radio did not go; similar of what I had experienced in Colombia.

One of the local teachers invited Laura and me to his simple home some hours away from Kisumu where we met his wife and two sweet pre-school girls. We tour the isolated country school where his wife taught and we shared a meal with the family. The following morning, after Laura and I slept together in a small bed, we teased each other on how this experience strengthened our bonds forever.

The IDEA Congress also offered us to visit a village of “cultural houses” (that’s how locals call an Indigenous community) where elderly women in colorful dresses welcomed us with an impressive chorus, strengthening the rhythm with their batons. During the long walk to reach this village, children were happily running like butterflies all around, curious about us, which made a Canadian teacher exclaim: “How is it possible that these children, who are unsupervised, behaved so well while our students don’t, if we stop looking at them a single minute?” From my own experience in Colombia, particularly in rural areas, I observed that the children from the village we were visiting were not really “unsupervised” because every neighbor was paying attention and elders were interacting with everybody all the time. I just thought about this as an example of the role of schooling in Western society, where intergenerational relationships get lost and how much we still need to learn from Indigenous cultures where “the village is an educator,” as current literature supports (Kanu, 2006; Sarangapani, 2003).

Laura: When I went to Kenya I was developing a theatre book for the 4H (Head, Heart, Hands and Health) — an international club for young peoplev. The organization began in the early 1920’s for isolated rural youth in the United States. I had been active in 4H as a young person. Our small club won the state prize for the best play when I was sixteen. In the last two decades 4H has expanded to include boys and girls in inner cities, moving far beyond livestock and home making. My goal for the book was to write a manual for an adult leader who was new to theatre. It would be a guide to develop a youth troupe that would be able to explore problems in their community through theatre. The book would include many improvisational techniques that I had used for years in teaching acting. The community part of the book would be based on Augusto Boal’s theories with a variety of Dorothy Heathcote’s drama techniques.

Zayda: Seeing the complex cultural diversity in Kenya reaffirmed my conviction on the importance of dramatic play, not only as a pedagogical but also as a qualitative research interpretive practice to understand children’s lives in different cultural contexts. I had already learned that children use dramatic play not only to represent events from reality as they are (As If), but to play with possible worlds, that is, the representation of non-existing, dreamed, or wished realities (What If) (Bretherton, 1984). Thus, through dramatic play children not only learn to reconstruct what exists, but also to envision transformations of reality. Learning how children portray characters, actions and their relations through dramatic play could also be understood as an interpretive practice: “through which reality is apprehended, understood, organized, and represented in the course of everyday life” (Gubrium & Holstein, 1997, p. 114). From the IDEA Congress I came back determined to learn more on how children from diverse contexts represent their world (real and dreamed) through pretend play.

New Transformations

Laura: At the time of the Congress I was facing a turning point in my life. I would be retiring in 1999, transforming from being a leader in my field to a housewife. I felt a sense of relief and freedom as I would not have so many obligations, and yet there was a void before me and I wondered where I would find a challenge equal to my energies. I found that challenge. In 1999 I founded and have been working for an organization called Fabulous African Fabrics, an international Non-Governmental Organization that grew directly out of my experiences at the Kenya IDEAvi. I had purchased some beautiful African textiles I used in the performance art piece at the Congress. These I took home and made Christmas presents for friends, the first step in developing an organization that is thriving today. This new mission changed my life, and the lives of hundreds of others. Based in Michigan with members in the United States, Canada, Trinidad and Tobago and the UK, FAF has raised $99.000 for Women Fighting AIDS in Kenya and The Good Samaritan Children's Home. In 2010 we became a part of an international organization of organizations, Global Giving, which helps small NGOs raise funds on line. In the beginning our central method of raising money was through making items of African textiles sewn into contemporary patterns. These we sold at craft fairs throughout the United States. Fundraising now takes many forms, but the central method of supporting the orphans is through direct donations. My love for children changed from playing with them, to changing their lives physically.

I settled into new hobbies: watercolor and silk painting; care for my autistic grandson; playing the steel drum, and knocking on doors for my favorite political candidates. Both of the books I was working on when I was in Kenya have been published: Making Performance Art (Salazar, 1999) and Youth Take the Stage (Salazar, 2010) which can be accessed on line.

Zayda: Getting back to my country after I finished my doctoral studies –and concerned by the non-existent articulation between Colombian school life and students' realities–, I founded DIVERSER Research Group (in Pedagogy and Cultural Diversity) at Universidad de Antioquia, which I led from 1999 to 2011. Through different grants we developed participatory projects with teachers, students, and community leaders from diverse cultural contexts (Afro, Native, Mestizo, Rural, and Urban). Some of the initiatives were the Semilleros de Investigaci6n (Young Researchers Program) (Sierra, Rojas, & López, 2010), the creation of an M.A. in Pedagogy and Cultural Diversity and a Ph. D. in Education and Intercultural Studies and several projects to unveil the situation of Indigenous students in Colombian universities (Sierra, 2004), which in turn lead us to the creation of a B.A. in Pedagogy of Mother Earth in partnership with the Indigenous Organization of Antioquia (OIA).

Decolonial theories and emancipatory pedagogy from Latin America –as the ones from Paulo Freire and Augusto Boal–, have served me to deconstruct dominant oppressive perspectives in my society and envision new possible worlds in education (Sierra, 2010). Through each project I have been looking at developing curricula more sensitive to communities' needs, recognizing class, gender and ethnic prejudices in daily interactions. Dramatic play has also shown to be a very suitable way to capture children's voices on how they envision life in their community, as well as an active learning process that stimulates their cognitive, creative, and social development (Sierra & Romero, 2002).

Laura: My latest transformation through drama came last winter at age 78. I joined a group of senior citizens who stage short plays for the community. I was astonished to discover at my first meeting that these actors have great talent, heart and dedication. The theatre experience is not just about some vapid, ego-centric pastime as I thought it would be. Their drama experiences lift them from a life of repetition and decline, and transform them to the thick of the human comedy and tragedy. Drama provides purpose to their existence. About 15 years ago a nation-wide movement began to encourage senior citizens to develop their own theaters. Groups write and perform their own plays and musical theatre and the growing body of plays written for senior citizens. The group I have recently joined is located at a Senior Center in San Jose, California. The ten women and two men are led by a volunteer director who is also a senior citizen. In this group almost all of the people have been active in community, professional, and university theatre throughout their adult lives. I am directing The Reading Club written by Patricia Callan, based on her narrative poem about a group of educated women in 1880s who form a reading group to help them keep their minds active while they are engaged with families and homemaking. Our actors like to portray characters who are younger than they are as well as elderly characters. The play will tour to churches, libraries and community groups in San Jose. Next year my goal is to work with the players as they dramatize scenes from their own lives.

Zayda: Currently I am working at Universidad de Antioquia on the design of a project titled "Toward sustainable rural communities with equity and diversity"vii, which I hope will contribute developing higher education programs in this field in Colombia. I also keep using dramatic play as an enjoyable qualitative research strategy when working with participants from diverse cultural contexts to unveil and interpret problematic situations that affect their communities and to look toward alternatives, while at the same time strengthening their leadership and communication skills.

Learning From This Dialogue; Some Questions and New Challenges

Going back to what each one of us wrote, re-structuring (and abbreviating) the paper each time after our dialogue via Skype, we want to underline several aspects we found in common, more as questions and new challenges than final remarks.

-

Why telling our story? Isn’t it an egotistical exercise? Well, we assumed that if it was good for us to learn from other people’s efforts, some others could find it interesting to learn about our own searches toward opening creative spaces for all children and adults –not just gifted ones– at a time when being critical and creative was not widely accepted in our societies, especially through dramatics. This open dialogue is a way to pass the torch of a very enjoyable and worthy life activity.

-

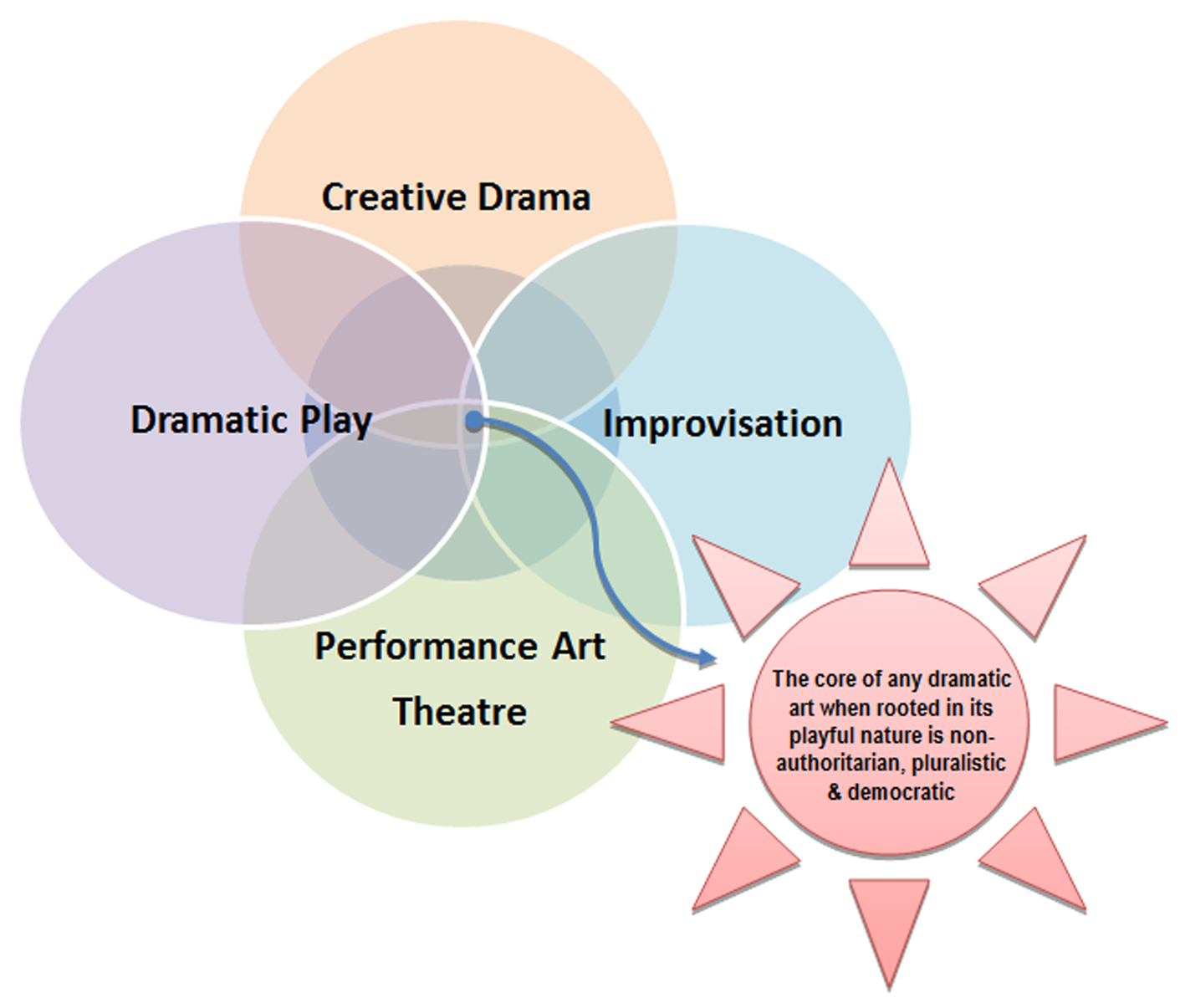

We decided to explore the educational potential of dramatic arts for everybody, not only for those who want to be professionals in theatre or the entertainment industry. Here is where we find the transformational core of any dramatic arts: its playful and free nature. Teachers, leaders and players need to learn how to negotiate their points of view and creatively motivate each other to get actively involved in the dramatic arts because play does not unfold if forced or in any authoritarian setting. See Figure 1 below:

Click to enlarge

Figure 1

The transformational qualities of dramatic arts.

-

An authoritarian approach provides people few options to communicate their understanding of the world as usually happens in most school environments, where students are expected to repeat what pre-defined official curricula says, without regarding the context where they interact and live. Social transformations are not going to occur if students are taught to be passive and submissive. Participative democracy is impossible if citizens are not allowed to think for themselves or are afraid to speak out their ideas. Therefore, we strongly believe that dramatic arts from a playful approach contributes to transform children and adults into open-minded thinkers, which in turns contributes to building a more pluralistic and democratic culture.

-

For us, any dramatic art needs a playful atmosphere to unfold to achieve the active involvement of participants and leaders. Play enriches and gives meaning to common people’s lives, helping everybody to change perspectives and grow socially. We believe that this educational potential of dramatic arts contributes to transform children from being passive consumers of the entertainment industry to being active builders of possible worlds. From our experiences in different contexts (Colombia, Kenya, United States) we have seen how dramatic expressions contribute to build a sense of community, largely lost in a consumerist and individualist society.

-

Dramatic arts also encourages a better understanding of cultural diversity and what it means to have a pluralistic society via facilitating participants to explore different situations, characters, stories, plots, scenarios, and historical times. As Koste (1978) said, pretending is a perfect “rehearsal for life.” Future studies should be devoted to understanding cultural diversity through pretend play and any other dramatic arts.

-

Working in organizations, educational institutions and our universities toward opening spaces to include dramatic arts in the curricula has also been part of our lives. Although difficult, we feel that it has been worthy; we are part of a global social movement to transform the compulsory aspect of schooling toward more democratic and creative educational processes, either in formal or non-formal settings.

-

Finally, why did we, as academic women, become devoted to motivate people’s expression through dramatic expressions? We both witnessed in our different environments how young men get involved in aggressive wars they do not ask for. Is it possible to build a better world through creative means? As many women and mothers in the world, we want our children and grand-children to grow up in societies that teaches them to find peaceful ways to deal with conflicts. As first women in our families to reach doctoral studies, we decided to put our expertise into this endeavor.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (